History In The Making, On The Roadside

For the last six months, farmers from Punjab and Haryana are on the roads bordering India’s capital city Delhi. Recently, ace Punjabi activist-journalist Hamir Singh was out on the road, as is often his wont, meeting some of the characters in this farmers’ agitation who rarely make it to even news headlines, what to talk of historical chronicles of any movement. This is a story of such characters – people who make history in which our future generations will live, but who will be unknown to them forever. The author invites you to walk with him and meet the characters who will never be in your history books.

![For the last six months, farmers from Punjab and Haryana are on the roads bordering India’s capital city Delhi. Recently, ace Punjabi activist-journalist Hamir Singh was out on the road, as is often his wont, meeting some of the characters in this farmers’ agitation who rarely make it to even news headlines, what to talk of historical chronicles of any movement. This is a story of such characters – people who make history in which our future generations will live, […]](https://www.theworldsikhnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Kisan-Andolan-360x266.jpg)

HAVING NURTURED FOR DECADES AN EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM in which kids find the subject of history boring and punctuated with dates and years. History then becomes a list of events related to kings and queens and those who challenge them to become kings and queens themselves. So, people’s understanding of history is reduced to when someone became a king, attacked another king, produced a child who became a prince and was then destined to become the next king, or what happened when a king died and his sons fought over the kingdom.

This is the most prevalent, and the most stupid, classical notion of history. It excludes the people. This approach does not tell us how the farmers lived during king X’s period, or how many little kids died of which diseases during king Y’s period, or how women suffered patriarchy under all the kings and even under the regimes of queens.

Not history, but a people’s history could have given answers to these relevant questions, but alas, we lag in the tradition of writing people’s history. Historiography remains a prisoner of kingly and queen-ly tales, but every era, every war and every movement throws up its heroes who do not find a place in our history books but who are real heroes of the people.

Historians and penpushers ignore them, but they live on in people’s minds, in folk songs, in myths and tales that define us. These heroes do not work with an eye towards getting into your NCERT books, nor do they hanker after Padma Awards. They don’t even want to become a TikTok sensation or a Twitter trend.

And they are much easier to meet and talk to than any leader. They are not VVIPs you try and get close to for a single selfie. Neither do they have a posse of gunmen to impress upon you their stature. But they are creating history. They are re-writing history. They are deciding history. So committed are they to their mission that they are ready to sacrifice their life for their goal.

And they are much easier to meet and talk to than any leader. They are not VVIPs you try and get close to for a single selfie. Neither do they have a posse of gunmen to impress upon you their stature. But they are creating history. They are re-writing history. They are deciding history. So committed are they to their mission that they are ready to sacrifice their life for their goal.

While many in India and abroad are trying to fashion certain people into heroes of the ongoing Kisan Andolan —waging campaigns on social media, pooling in funds and not just appearing on TV channels but also launching some channels of their own —some of our singers, artistes, writers, intellectuals and those with self-serving political agendas are also dying to get themselves anointed as the biggest benefactors of the farmers’ movement.

But amid all of this cacophony, working in their own silent and dedicated ways, are the real heroes of the Andolan. Travel along the historical road built by Chandragupta Maurya, improved by Samrat Ashoka and rebuilt by the likes of Sher Shah Suri, the Mughals and the British, and you will run into these heroes every few miles.

But amid all of this cacophony, working in their own silent and dedicated ways, are the real heroes of the Andolan. Travel along the historical road built by Chandragupta Maurya, improved by Samrat Ashoka and rebuilt by the likes of Sher Shah Suri, the Mughals and the British, and you will run into these heroes every few miles.

Hardly anyone pays attention to these heroes, even though they are the foundation on which a mammoth Kisan Andolan is pivoted today. The entire edifice of this challenge to the regime rests on this foundation. They bear the burden of an agitation, keeping it alive, robust and throbbing with energy, but without making noise or headlines.

Meet Harbhajan Kaur. Look at her face in this picture. Notice the symbols of Sikhism hanging as a pendant from her neck. Do not miss the black ribbon of protest tied to a bamboo pole behind her head. The little plastic bottle tied with a string. Browse through the other pictures of Harbhajan Kaur. Notice the political ideology scribbled on the homemade buntings. Let your eye rove over the thatched bamboo-straw roof. Stop and stare at the 6 x 3 feet folding bed that remains bare. Marvel at how much of the world do they need as you see all the stuff they require in the two improvised baskets that hang from the ceiling. Please do not skip noticing their social connectivity –the newspapers, the most basic of the non-smartphones, and their readiness to welcome even more guests into their kingdom. That’s why there’s a spare folding bed stacked next to the bamboo pole.

So much to notice in just these quickly snapped pictures. And you see an invitation to yourself. Tikri Aao. Come to Tikri, says a pennant in the string. A poster nailed to a bamboo brings Safdar Hashmi into Harbhajan Kaur’s kingdom, proclaiming:

किताबें करती हैं बातें बीते जमानो की,

दुनिया की, इंसानों की,

आज की कल की, एक-एक पल की,

खुशियों की गमों की,

फूलों की बमों की,

जीत की हार की, प्यार की मार की,

सुनोगे नहीं क्या किताबों की बातें।

किताबें, कुछ तो कहना चाहती है,

तुम्हारे पास रहना चाहती है।

Of course, in Harbhajan Kaur’s kingdom, these lines are in the Gurmukhi script. She understands Hindi but can read the Punjabi script.

And when you are noticing and reading all of that, there’s still something more important that you just cannot miss: the ten thousand wrinkles on Harbhajan Kaur’s face. Her bare-bones threatening to tear their way out of her flesh. Her frail physical being. Her fiery eyes. Her sharp gaze. Her clear understanding of what is happening, how is the war front shaping up, and what might befall the Kisan Andolan.

And she knows it all depends upon her. And upon many others like her.

Harbhajan Kaur comes from the grass that grows in Barnala’s countryside.

‘Passengers will ask the bus conductor / ‘Where are we? Drop us at Barnala / Where the green grass grows thick.’

Hailing from Barnala’s Mehal Khurd village, Harbhajan Kaur has seen 80 summers and 80 winters, and innumerable rulers promising to change the face of agriculture and turn Punjab into California but is too rooted to fall for any of it. When the Kisan Andolan began, Harbhajan Kaur must have instinctively known that it will be difficult to fight all of it on Twitter. She knew the Andolan needed her. So she, along with her friend Raminder Kaur of the same village, landed up at Delhi’s Tikri border. She brought along very little stuff, but a big decision: she won’t go back without a victory.

Hailing from Barnala’s Mehal Khurd village, Harbhajan Kaur has seen 80 summers and 80 winters, and innumerable rulers promising to change the face of agriculture and turn Punjab into California but is too rooted to fall for any of it. When the Kisan Andolan began, Harbhajan Kaur must have instinctively known that it will be difficult to fight all of it on Twitter. She knew the Andolan needed her. So she, along with her friend Raminder Kaur of the same village, landed up at Delhi’s Tikri border. She brought along very little stuff, but a big decision: she won’t go back without a victory.

This is how real history is made; people like Harbhajan Kaur bring along a resolve to overturn the decisions of regimes led by the likes of Narendra Modi. When history will be written, you will read about Modi, but NCERT books won’t tell you about Harbhajan Kaur: mother to three sons and a daughter; hailing from a well-off rural family; a son settled in Canada.

She does not need any Sarkari dole. She does not need Modi’s mercy. Her kids have 15 acres of land each. She has been to Canada twice. She keeps a phone by her side because her son sometimes calls. “Mother, you’ve marked your presence at the Andolan. Now, you should go back home. Stay in the village.” He is worried. Modi’s is not a very people-friendly regime, and there’s Covid in the air. Harbhajan Kaur is old and frail. But her spirit isn’t.

“I am staying put here only, in this hutment on the Tikri border. Anyone who wants to meet me is most welcome to come here, but don’t tell me to go back. This is my new village. My Mehal Khurd – bang on the Tikri border!”

Modi can’t understand this resolve, but Pash will very easily find this new Barnala village on Delhi’s border. Resolve is growing, some green grass, too. And Harbhajan Kaur now lives here – the soul and spirit of what people’s history looks like.

When relatives exerted too much pressure, she did make an exception and went back to her village. It was her grandson’s Lohri. Family members tried to prevail upon her to stay back, but Bebe Harbhajan Kaur picked up some Rs 10,000 in cash, gathered a few more utensils and stuff she might need, and was back in her new village to challenge the regime run by macho men. This time, she felt even more relieved.

“I have given everyone my blessings.”

‘ਸਭ ਦੇ ਸਿਰ ਪਲੋਸ ਕੇ ਆਈ ਹਾਂ। ਅੰਦੋਲਨ ਜਿੱਤ ਗਿਆ ਤਾਂ ਸਨਮਾਨ ਕਰ ਦੇਣਾ, ਨਹੀਂ ਤਾਂ ਅਰਥੀ ਨੂੰ ਕੰਧਾ ਦੇ ਦੇਣਾ… ਇਹ ਹੁਣ ਇੱਜ਼ਤ ਦਾ ਸੁਆਲ ਹੈ।’

“I placed my hand on everyone’s head. If the Andolan wins, felicitate me, or stay ready to be my pallbearer…From here onwards, it is a question of honour.”

She said she has worked too hard in her life, and it is not easy for anyone to leave behind the comforts and a happy, prosperous extended family and spend her fag years in biting-cold or scorching sun, sleeping with mosquitoes buzzing in the humid air, but it’s a question of izzat, of honour.

“I have given everyone my blessings.”

‘ਸਭ ਦੇ ਸਿਰ ਪਲੋਸ ਕੇ ਆਈ ਹਾਂ। ਅੰਦੋਲਨ ਜਿੱਤ ਗਿਆ ਤਾਂ ਸਨਮਾਨ ਕਰ ਦੇਣਾ, ਨਹੀਂ ਤਾਂ ਅਰਥੀ ਨੂੰ ਕੰਧਾ ਦੇ ਦੇਣਾ… ਇਹ ਹੁਣ ਇੱਜ਼ਤ ਦਾ ਸੁਆਲ ਹੈ।’

“I placed my hand on everyone’s head. If the Andolan wins, felicitate me, or stay ready to be my pallbearer…From here onwards, it is a question of honour.”

Bebe Harbhajan Kaur and her friend Raminder Kaur tell tales that bring alive contemporary history. One of Harbhajan Kaur’s fellow villagers was a man called Master Darshan Singh who later shifted to nearby Mehal Kalan. Master Darshan Singh’s daughter Kiranjit Kaur, a student of 10+2, did not return home one day in July 1997. Later, it came to light that she was waylaid, kidnapped, raped and murdered by goons who had political influence and links. Her body was exhumed from the fields where it was buried, triggering an Andolan that redefined what a collective people can achieve.

The Kiranjit Rape and Murder Case made history. The movement it triggered was a revolution of sorts, turning into a clarion call to fix what is wrong with our democracy. A quarter-century later, the Kiranjit Kaur Mehal Kalan Tragedy Protest Action Committee continues to do its work even today.

The Kiranjit Rape and Murder Case made history. The movement it triggered was a revolution of sorts, turning into a clarion call to fix what is wrong with our democracy. A quarter-century later, the Kiranjit Kaur Mehal Kalan Tragedy Protest Action Committee continues to do its work even today.

If your idea of the history of Punjab has remained limited to what they teach you in history books in schools, then you might possibly have not heard of Kiranjit Kaur Rape and Murder Case or the movement in its wake that took Punjab by a storm. But Harbhajan Kaur and Raminder Kaur did not learn history from textbooks. They were busy making it.

If your idea of the history of Punjab has remained limited to what they teach you in history books in schools, then you might possibly have not heard of Kiranjit Kaur Rape and Murder Case or the movement in its wake that took Punjab by a storm. But Harbhajan Kaur and Raminder Kaur did not learn history from textbooks. They were busy making it.

Both of them were part of that movement, actively participating in the protests -dharnas, rallies called by the Action Committee. Raminder Kaur came to Tikri with Harbhajan Kaur, and since then, hasn’t visited her village even once. She had gotten married in village Rama of NihalSinghWala in Moga, but her husband passed away after eight years of marriage. The in-laws refused to honour her right to any property, and she returned to her parents in Mehal Khurd.

Both of them were part of that movement, actively participating in the protests -dharnas, rallies called by the Action Committee. Raminder Kaur came to Tikri with Harbhajan Kaur, and since then, hasn’t visited her village even once. She had gotten married in village Rama of NihalSinghWala in Moga, but her husband passed away after eight years of marriage. The in-laws refused to honour her right to any property, and she returned to her parents in Mehal Khurd.

She did not need to learn the notions of patriarchy from textbooks of sociology. Patriarchy had decided her life’s course. She knew a young Kiranjit very well. “Kiranjit Kaur of Mehal Kalan was our nephew’s daughter. Till 10th grade, she and my daughter Manjit Kaur were classmates.”

When Kiranjit Kaur was raped and killed, she became part of the movement. Later, when one of the leaders of the agitation, Manjit Dhaner, was embroiled in a case and sentenced to jail, she remained in the forefront of the protests, sitting in front of the Barnala courts all day to demand that his sentence be commuted.

When Kiranjit Kaur was raped and killed, she became part of the movement. Later, when one of the leaders of the agitation, Manjit Dhaner, was embroiled in a case and sentenced to jail, she remained in the forefront of the protests, sitting in front of the Barnala courts all day to demand that his sentence be commuted.

“We are not people who will go back without the government taking a decision,” she said.

She knows how they write history in a dishonest manner; she is adamant about making some with honest direct people’s action.

The day I visited them in their make-shift hutment with the Pash poster, folding beds, revolutionary buntings and Himalayan resolve, they were the only two women from Mehal Khurd. The men had returned to their village to look after the wheat harvest and were still to return. A young man, Balkar Singh from Sangrur’s Ealwal (ਈਲਵਾਲ) village, has become their handyman, a comrade-in-arms.

Balkar Singh has left behind his wife and two kids, apart from his brother in his village, and is staying put in the tent city that Tikri Border of Delhi has become in six months. He says he will be looking after the safety and security of Harbhajan Kaur and Raminder Kaur till their own people from Mehal Khurd return to the border. “The Andolan is resulting in new relationships, new ties of kinship. People find peace and contentment in becoming useful to each other. The loss feels lessened,” Balkar Singh told me.

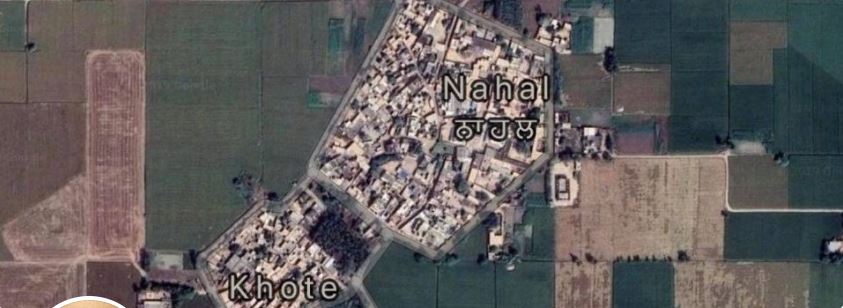

A little ahead I ran into a young man from Moga’s village Nahal Khote. He has a strange name — Jagga Kanhaiya. Everyone with even a passing acquaintance with Punjabi or Sikh history knows about Bhai Kanhaiya. When cops were raining lathis and governments welcomed the citizens asking for their rights with tear gas shells, there were some who were seen serving langar and water to even the police – the personification of the ideology of Bhai Kanhaiya.

Jagtar Singh was someone like those youth, always ready to help. Jagga Kanhaiya is a name he earned at the Tikri border. After his soldier brother’s death, Jagtar, who was running his shop in Maharashtra’s Nagpur, wrapped up his business and came back to look after his parents in the village. Then the Kisan Andolan happened. There was no Bharti Kisan Union unit in his village. The Ekta-Ugrahan leftist BKU now has a unit. A lot of water has flowed in the Yamuna since the fateful November 26th of 2020 when a sea of humanity had landed up at Singhu and Tikri borders, but Jagtar Singh-turned-Jagga Kanhaiya has not looked back.

His brother-in-law (sister’s husband) passed away; then his cousin died, then another relative, but Jagga Kanhaiya has remained at Tikri border. He is alone these days, along with the trolley. Sewa is his mission. Much of his time is spent making arrangement for water for others nearby. I am sure he knows he will not be there in any future historian’s account. No list of India’s heroes will have his name or picture. But I saw him there –a hero in people’s unwritten but lived history.

They come by the dozen on the borders of Delhi these days. Sometimes with a stethoscope dangling around their necks. Meet Dr Swaiman Singh. His first name literally translates into ‘self-respect.’ When the reverberations from the Kisan Andolan crossed the Indian and Atlantic oceans and hit the United States of America, Dr Swayaman Singh responded to his inner being’s call. He realised the Andolan needed the hands of a professional doctor.

A cardiologist by training, he knew what life on the borders under open skies and fighting against elements of nature amid a raging pandemic can do to human bodies. He landed at Tikri, and immediately went about setting up a village called – hold your breath – “California.” It was an under-construction bus stand at Bahadurgarh.

Now, it boasts of a team of more than 30 volunteer doctors, and hundreds of paramedics ready to help. He does not keep himself limited to matters of cardiology; he knows dil da maamla goes much beyond angioplasties and angiographies. He is here with a heart. When the trolleys no more served the intended purpose, he came up with the idea of raising structures built around reinforced angle-irons or bamboos. So far, he has made 1,100 such structures, and 400 more are in the works.

Dr Swayaman Singh backs the vaccination drive but opposes mandatory testing for the virus. He knows the motives are not medical, but political. “The government will use the tests as a tool to claim that pandemic was raging because of the Andolan and it can go to any extent. If they want to vaccinate people, they should involve us and we will do the needful,” he said.

Dr Swayaman Singh backs the vaccination drive but opposes mandatory testing for the virus. He knows the motives are not medical, but political. “The government will use the tests as a tool to claim that pandemic was raging because of the Andolan and it can go to any extent. If they want to vaccinate people, they should involve us and we will do the needful,” he said.

When asked when he plans to return to the United States, where he has spent 24 years, he said: “That question does not arise till the Andolan is here. How can I leave these people in need and go back to my cushy life? I have enough life left to earn the moolah, let me do some sewa here first.”

When asked when he plans to return to the United States, where he has spent 24 years, he said: “That question does not arise till the Andolan is here. How can I leave these people in need and go back to my cushy life? I have enough life left to earn the moolah, let me do some sewa here first.”

A particular structure has come up for a lot of discussion in the media, attracting visitors from regions far and wide. A 25 feet x 15 feet mud house, with an attached bathroom, with some graffiti-style artwork on its outer walls embalmed with some cow dung and mud, it now becomes the backdrop for a lot of selfies and photo shoots. Jatinder Pal Singh was visiting home from New Zealand where he had emigrated some ten years ago, looking for a job and better opportunities.

A particular structure has come up for a lot of discussion in the media, attracting visitors from regions far and wide. A 25 feet x 15 feet mud house, with an attached bathroom, with some graffiti-style artwork on its outer walls embalmed with some cow dung and mud, it now becomes the backdrop for a lot of selfies and photo shoots. Jatinder Pal Singh was visiting home from New Zealand where he had emigrated some ten years ago, looking for a job and better opportunities.

On his visit home to Mohali, he encountered the Kisan Andolan. It was not difficult for him to understand that the Andolan was actually for him. The Andolan was trying to protect a way of life and the vocation of agriculture, and if it did not succeed, then future generations will lose whatever they have and will become eternal emigrants like him.

This was his fight. He was not going back to New Zealand anytime soon. The Andolan was making history and he was to play a role in it. Of course, it will not be in the textbooks that your children will read unless his people won and re-wrote the very approach to history.

Jatinder joined some others to take up the responsibility of security of the protestors at the border, then got into conceiving and designing the mud house that could give some respite to his people. The emigrant/immigrant is at home now – it’s just a mud house, but it is making some history.

Jatinder joined some others to take up the responsibility of security of the protestors at the border, then got into conceiving and designing the mud house that could give some respite to his people. The emigrant/immigrant is at home now – it’s just a mud house, but it is making some history.

The much-famed library at the Kisan Andolan is also doing the same. Initially, it was just a bunch of books placed on a cot. Some bright minds knew the Andolan would need a strong, cerebral dimension. They saw the crowds pulling out barricades as people trying to break through the shackles in search of a renaissance — so they brought books to the movement. The library is now a sort of think tank at the Andolan. It is a place for some serious brainstorming, lectures, workshops, a reading centre. It does the same thing that Pash’s poster is doing in the hutment of Harbhajan Kaur and Raminder Kaur.

किताबें करती हैं बातें बीते जमानो की,

दुनिया की, इंसानों की,

सुनोगे नहीं क्या किताबों की बातें।

किताबें, कुछ तो कहना चाहती है,

तुम्हारे पास रहना चाहती है।

Sukhvinder Singh from near Anandpur Sahib and his friends are keeping alive the great tradition of Punjabi ‘satth’ (ਸੱਥ) where debates and discussions happen all the time. Every night at 8, an hour and a half long engaged structured talk about a topic to underline how the Andolan understands its place in history and is alive to how future historians will see it. Sukhvinder’s team invites academicians and scholars to come and talk to them and spread the word about any visiting intellectual.

As you drive along the National Highway 44, which earlier used to be called NH1, you cannot miss the tent on your left-hand side just next to the Panipat Toll Plaza. This is the long-running Langar for the protestors and all those who care about the history in the making. The battles fought in Panipat have decided the fate of this country for centuries. This one is no less. The langars are crucial to the battle, and people like Balvir Singh of nearby Faridpur village know it. He owns eight acres of fertile land, but much of his time is spent doing sewa at the langar.

Kings and queens will occur in school syllabi and your children will find them dead and boring and will ignore them. The likes of people I met on the road and at Singhu and Tikri borders are those whose tales, songs, stories and dreams will shine a light in our lives.

After the controversial incidents of January 26 this year, the police had shut down the langar for one day, but battles in Panipat are fought hard and bitter. The langar was soon back to play its role in history.

After the controversial incidents of January 26 this year, the police had shut down the langar for one day, but battles in Panipat are fought hard and bitter. The langar was soon back to play its role in history.

I ran into many ordinary people sucked in by the agitation. I met Mukhtiar Singh Waraich, Mukhtiar Singh Virk, Joginder Singh Waraich, Kuldeep Singh, who all told me how many farmers have harvested wheat and donated a major chunk of it for the Andolan. Then there is a Shah Family that came from Nankana Sahib in 1947. They have given the farmers a carte blanche that any time ration is needed, they can buy it in the family’s name. Chaudhury Varinder Shah’s father has remained an MLA for five terms. His elder brother, too, was an MLA. Varinder Shah, popularly known as Bulleh Shah, says his family has everything by the blessings of Guru Nanak. They haven’t put up a banner, haven’t affixed their picture anywhere. Like Harbhajan Kaur, they are also not looking for a place in your history books.

But they are making history — the people’s history. One in which our future generations will live.

Kings and queens will occur in school syllabi and your children will find them dead and boring and will ignore them. The likes of people I met on the road and at Singhu and Tikri borders are those whose tales, songs, stories and dreams will shine a light in our lives.

The Kisan Andolan is never been history. It will always keep redefining history. History is happening right in our times. It is no more a tale from the past. It is our present, and it is your future. It is entrenched at the border, and Delhi is still to make its mind after more than six months, or perhaps many decades too late.

The battle is raging, and Harbhajan Kaur’s name will be in the leading cavalry. A cell phone in hand, the khanda-kirpan pendant around her neck, the thousand wrinkles crisscrossing her face and her gaze straight at the goal. It is a question of self-respect. And that has often turned history around.

Translated and adapted by Senior Journalist SP Singh from the author’s original Punjabi iteration published in the Punjabi Tribune on June 1, 2021. This version has been authorised, vetted and approved by the author. — Editor

Senior journalist Hamir Singh is widely read and respected for his grasp of the economic, political and societal aspects of Punjab’s rural countryside as well as skewed patterns of what is often referred to as ‘vikas’ -progress, in our times. Months back, he was among the first ones to perceive the threat inherent in the three agriculture-related pieces of legislation rammed through in Parliament by the Modi government. Hamir Singh has since written innumerable articles, done ground reporting from the grassroots, made several visits to the battlefronts along Delhi’s borders besides continuing with his work among the masses. With his journalism, activism and role as a citizen often enmeshed with each other, his is a voice that is often taken as a definitive one on the issue.

Senior journalist Hamir Singh is widely read and respected for his grasp of the economic, political and societal aspects of Punjab’s rural countryside as well as skewed patterns of what is often referred to as ‘vikas’ -progress, in our times. Months back, he was among the first ones to perceive the threat inherent in the three agriculture-related pieces of legislation rammed through in Parliament by the Modi government. Hamir Singh has since written innumerable articles, done ground reporting from the grassroots, made several visits to the battlefronts along Delhi’s borders besides continuing with his work among the masses. With his journalism, activism and role as a citizen often enmeshed with each other, his is a voice that is often taken as a definitive one on the issue.

One thought on “History In The Making, On The Roadside”