Maharaja of Punjab plans to loot poor man’s village lands

Extraordinary situations created by sinister policies and proposals must be met with sane responses and intelligent rebuttals. The farfetched proposal of Maharaja Amarinder Singh to loot the lands of the poor peasantry of Punjab and give it to rich landlords, businessmen, nouveau-riche entrepreneurs is fraught with the danger of destroying the landscape and nature of Punjab. Ace journalist and TV commentator S P Singh traces the history of the Land Acquisition Act over the decades, thrashes out the concerns of the common man and rubbishes totally the sinister proposal of the Amarinder Singh government in the Indian state of Punjab to forcibly acquire Village commons -Shamlat land and distribute it virtually for peanuts in the name of Punjab Rural Industrial Revolution. Extraordinary issues require vastly extraordinary and extensive reporting. Your deep indulgence is solicited to sit through and digest this long piece of investigative reporting which will leave you armed with enough material to stand up for the rights of the poor and stand up to the wayward attitude and feudal functioning of the ruling Maharajah of Patiala, er..Punjab.

![Extraordinary situations created by sinister policies and proposals must be met with sane responses and intelligent rebuttals. The farfetched proposal of Maharaja Amarinder Singh to loot the lands of the poor peasantry of Punjab and give it to rich landlords, businessmen, nouveau-riche entrepreneurs is fraught with the danger of destroying the landscape and nature of Punjab. Ace journalist and TV commentator S P Singh traces the history of the Land Acquisition Act over the decades, thrashes out the concerns of […]](https://www.theworldsikhnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/amarinder-360x266.jpg)

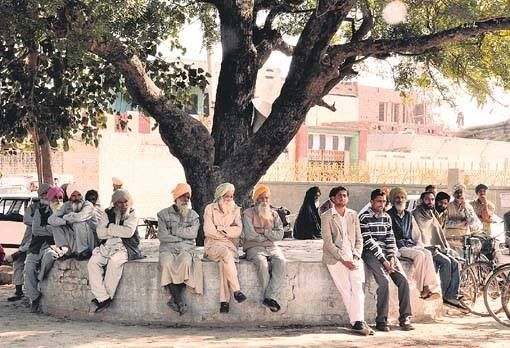

ONE FINE EVENING IN 2003, A GROUP OF VILLAGERS, in a sleepy village in Punjab’s Patiala got into a tiff with a fellow villager who was trying to build a house on the shamlat land, the common land of the village. It could have been settled through discussions under a banyan tree or perhaps a scuffle near the street corner, but instead, it ended up impacting all the villages in all the districts of all the states in all of India.

Now, the Amarinder Singh government wants to effectively upturn an apex court judgement, wisdom, impact and reasoning, but since the issue is not as emotive as the SYL Canal-blocker Termination of Agreements Act 2004, therefore, it has not made too many waves in the media.

The Punjab government is now guilty of opening the doors of the collective wealth of Punjab for loot by the land sharks, but more than that, its planned move will forever change what our villages have been for centuries. Punjab will never be the same again if the Amarinder Singh government is allowed to get away with its nefarious design. In fact, there will be no villages left.

Lest you think we are overstating our case, let me assure you that we could, in fact, be guilty of understating the threat. Also, the Amarinder Singh government is hell-bent on blowing to smithereens the entire logic built up by Rahul Gandhi against the Land Acquisition Act that the Modi government wanted to push through but couldn’t.

But the story started way back on that evening in 2003 in village Rohar Jagir in Patiala when Jagpal Singh was trying to extend his house on a piece of Shamlat land, or Village Commons.

Jagpal Singh’s argument was that other people of the village had also extended their houses on the same common land, but the group of villagers opposing him argued that the land was meant for the use of the collective.

The Amarinder Singh government is hell-bent on blowing to smithereens the entire logic built up by Rahul Gandhi against the Land Acquisition Act that the Modi government wanted to push through but couldn’t.

The gram panchayat of Rohar Jagir filed an application under Section 7 of the Punjab Village Common Lands (Regulation) Act, 1961, to evict the trespassers, including Jagpal Singh. It also went to the police and filed an FIR but the unauthorised occupants had the backing of officials and panchayat members. The Patiala district collector, instead of telling Jagpal Singh and his fellow encroachers to pack up and leave, held in his September 13, 2005 order, that doing so wouldn’t be in the public interest since they have already spent a lot of money on constructing their houses. He simply asked the gram panchayat that all it can do was to recover the cost of the land from the trespassers.

This was clearly a case of collusion in regularising illegality on the ground that encroachers had spent huge money on constructing houses on the usurped common land of the village.

The Punjab government is now guilty of opening the doors of the collective wealth of Punjab for loot by the land sharks, but more than that, its planned move will forever change what our villages have been for centuries. Punjab will never be the same again if the Amarinder Singh government is allowed to get away with its nefarious design. In fact, there will be no villages left.

The aggrieved residents appealed to the Development Commissioner who rightly ruled that regularising such illegal encroachment was not in the panchayat’s interest. In fact, in his December 12, 2007 order, he held that the Gram Panchayat had colluded with the encroachers since it neither opposed nor filed an appeal against Collector’s order that directed the Gram Panchayat to transfer the property to illegal occupants.

The trespassers went to the high court, which threw out the plea on February 10, 2010. A division bench also took the same view. The trespassers then appealed to the Supreme Court.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

The two sides to the dispute, as well the government of Punjab, thought the top court might decide one way or the other. Not in their dreams could they have imagined that the judgement would impact all of India. After all, it was just a tiff between Jagpal Singh and his fellow villagers in that sleepy Rohar Jagir village, just half an hour drive away from Moti Bagh Palace residence of the scion of Patiala Royale. Before this, Rohar Jagir’s whose great claim to fame was only that the local bus stopped there. Now, they ensured the buck went all the way up to the Supreme Court.

In its verdict on January 28, 2011, the Supreme Court said the appellants were, indeed, “trespassers,” that they had indeed illegally encroached on the gram panchayat land by using muscle power/money power, that the officials had colluded with the encroachers, and that even the gram panchayat was guilty of collusion.

It ordered that the land must be returned to the gram panchayat. “We cannot allow the common interest of the villagers to suffer merely because the unauthorised occupation has subsisted for many years,” the SC judgment said.

So far, so good. And then came the bombshell. The Supreme Court was told that the unauthorised possession of land by the likes of Jagpal Singh in that village was regularised by the Punjab government vide a letter dated 26.9.2007. The top court also took note of the fact that shamlat/common land in villages across India has been facing encroachments. It also noticed that a lot of state governments have been legally authorising such illegal actions.

Consequently, the Supreme Court said the Punjab government’s letter regularising the illegal possession of the land was invalid.

“We are of the opinion that such letters are wholly illegal and without jurisdiction. In our opinion, such illegalities cannot be regularized. We cannot allow the common interest of the villagers to suffer merely because the unauthorized occupation has subsisted for many years,” it said.

And then came the turn of the rest of India.

“In many states, Government orders have been issued by the State Government permitting allotment of Gram Sabha land to private persons and commercial enterprises on payment of some money. In our opinion all such Government orders are illegal, and should be ignored,” it said.

The judges were only warming up: “Our ancestors were not fools. They knew that in certain years, there may be droughts or water shortages… water was also required for cattle to drink and bathe in, etc. Hence they built a pond attached to every village, a tank attached to every temple, etc. These were their traditional rain water harvesting methods, which served them for thousands of years.

“Over the last few decades, however, most of these ponds in our country have been filled with earth and built upon by greedy people, thus destroying their original character. This has contributed to the water shortages in the country,” it said.

“Our ancestors were not fools. They knew that in certain years, there may be droughts or water shortages… water was also required for cattle to drink and bathe in, etc. Hence they built a pond attached to every village, a tank attached to every temple, etc. These were their traditional rainwater harvesting methods, which served them for thousands of years.

The SC also noted that ponds in villages across India were auctioned off at throwaway prices to businessmen for fisheries in collusion with authorities/Gram Panchayat officials, and said, “The time has come when these malpractices must stop…The time has now come to review all these orders by which the common village land has been grabbed by such fraudulent practices.”

What came next hit all of India:

“We give directions to all the State Governments in the country that they should prepare schemes for eviction of illegal/unauthorized occupants of Gram Sabha/Gram Panchayat/Poramboke/Shamlat land and these must be restored to the Gram Sabha/Gram Panchayat for the common use of villagers of the village.”

“The Chief Secretaries of all State Governments/Union Territories in India are directed to do the needful… Long duration of such illegal occupation or huge expenditure in making constructions thereon or political connections must not be treated as a justification for condoning this illegal act or for regularizing the illegal possession,” the Supreme Court said.

It also made it clear where regularisation can be permitted: “Regularization should only be permitted in exceptional cases, e.g. where lease has been granted under some Government notification to landless labourers or members of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, or where there is already a school, dispensary or other public utility on the land.”

“We give directions to all the State Governments in the country that they should prepare schemes for eviction of illegal/unauthorized occupants of Gram Sabha/Gram Panchayat/Poramboke/Shamlat land and these must be restored to the Gram Sabha/Gram Panchayat for the common use of villagers of the village.”

And after saying all of this in its judgement, the Supreme Court was not done. It not only ensured that “a copy of this order be sent to all Chief Secretaries of all States and Union Territories in India (to) ensure strict and prompt compliance” but also directed them to “submit compliance reports to this Court from time to time.”

Now, in the final para of the judgement, watch the determination of India’s top court: “Although we have dismissed this appeal, it shall be listed before this Court from time to time so that we can monitor implementation of our directions herein… all Chief Secretaries in India will submit their reports.” [Extract from order dated 28 January 2011 in Civil Appeal No.1132 of 2011; Bench comprising Justice Markandey Katju and Justice Gyan Sudha Misra]

* * *

NINE YEARS AFTER the Supreme Court judgement, and two and a half centuries after the Industrial Revolution that transformed Europe and the United States, and effectively the world, Punjab’s Amarinder Singh government has come up with a fantastic plan to usher in a Rural Industrial Revolution in the state. It involves a scheme that will facilitate setting up of industry and entrepreneur businesses in virtually every village of Punjab that has shamlat land.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

Just as the world was preparing to bid goodbye to 2019 and India was in the throes of an agitation against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC), and Rahul Gandhi was busy painting the Narendra Modi regime as the government of the Fascists, Amarinder Singh was working hard to facilitate this Rural Industrial Revolution.

On December 2, 2019, the Punjab Cabinet gave its in-principle approval to amend the Punjab Village Common Land (Regulation) Rules, 1964, thus allowing the panchayat to sell the shamlat land to entrepreneurs, businessmen, companies or whosoever can set up Micro, Small or Medium enterprises/industrial houses on that land. The proposal — pushed through the Rural Development and Panchayats Department which is primarily tasked with safeguarding the rights of the panchayats and preventing any usurpation of Village Commons — involves insertion of Rule 12-B in the ‘Punjab Village Common Lands (Regulation) Rules, 1964’, creating a special provision for transfer of Shamlat Lands for development of industrial infrastructure projects.

It is to be implemented by the Punjab Industry Department and the Punjab Small Industries and Export Corporation, a state-level PSU that is embroiled in a thousand controversies and whose officials in the past have been found involved in shady deals.

For the Panchayati land thus purchased through the PSIEC, the government has also come up with deferred payment terms. The industrialist/entrepreneur will only be obligated to pay 25 per cent of the cost of land upfront and can pay the rest in four annual instalments that will start after a two-year gap. The Cabinet lost no time in approving this amendment, in its words, “to create rural land banks for industrial development.”

The Amarinder Singh government’s reasoning is that it is using the Gram Panchayats to promote the development of villages by unlocking the value of Shamlat land.

“I’ll give you what you want… tell me what’s needed, I’ll do everything that is needed.”

Indeed, everyone knows what another well-wisher of villages, Mahatma Gandhi, said. “The future of India lies in its villages.” But not if the village panchayats sell their land!

Interestingly, and significantly, just three days after the Punjab Cabinet’s decision, CM Amarinder Singh stood before the moneybags at an elite educational and research institute dedicated to teaching how to make money and become a moneybag. At the jarringly-titled two-day (Dec 5-6, 2019) Progressive Punjab Investors’ Summit at the Indian School of Business in Mohali, Amarinder Singh said:

“I’ll give you what you want… tell me what’s needed, I’ll do everything that is needed.”

“Whatever we have done in our industrial policy or otherwise is not sacrosanct. If any of you require changes, we are quite prepared for it… I hope you go from here convinced that we are committed to your welfare. We will give you security, we will ensure peace for you…There are no labour problems in Punjab, no strikes.”

Not once has Amarinder Singh said to the farmers of Punjab: “I’ll give you what you want… tell me what’s needed, I’ll do everything that is needed.”

Some two-thirds of Punjab’s villages, 7,941 to be precise, have cultivable Shamlat land. Panchayats in Punjab auction the cultivable land and the money thus accrued, by a rough estimate about Rs 340 crore, is used for the development of the village. In a peculiar arrangement, Punjab’s fund-crunched government devised a blatant and inexplicable way to steal some of this money to pay off some of its employees. Through an executive order, it made it obligatory for the panchayats to give 20 per cent of the money earned through an auction of cultivable land to the Punjab Rural Development and Panchayat Department to pay the salaries of the employees.

So, effectively, the panchayats in Punjab have been paying the salaries and financing the perks enjoyed by the employees recruited by the Punjab government who are neither accountable nor report to the panchayats.

Even otherwise, Panchayats have invariably been administered by the government in a cavalier fashion, with the policy often tweaked by babus sitting in the secretariat with no claim of being in touch with ground realities. Rules and laws are formulated, changed or interpreted at the instance of the politicians who use influence, power and funds at their discretion to play one faction against the other and, thus, become the dispenser of favours. For instance, some time back, the Amarinder Singh government had framed new rules to revert to district-wise reservation of sarpanches, a change from its previous practice of reserving these constituencies block-wise. No public debate preceded the move, and not a single protest or agitation followed it.

Gandhi’s idea, after direct experience with the village life, was that “If the villages perish, India will perish, too. It will be no more India. Her own mission in the world will get lost.” (Harijan, August 29, 1936; 63:241.) Somewhere down the line, Amarinder Singh and his coterie decided that if villages perish, Punjab will thrive. But they forgot to tell us about their experiential and intellectual journey that brought them to this peculiar wisdom.

The panchayats in Punjab have been paying the salaries and financing the perks enjoyed by the employees recruited by the Punjab government who are neither accountable nor report to the panchayats.

Punjab government and the rural dalit populace have been in a battle mode over the latter’s right to one-third of the cultivable shamlat land. Dalits, with virtually no access to fodder or grazing lands, have been pressing their statutory right but, in actual practice, the upper caste landlords have been successful in thwarting all their efforts.

Among all Indian states, Punjab has the highest percentage (31.94%) of SC population, which is predominantly rural, with sizeable numbers living below poverty line. As per a decade old Agricultural Census (2010-11), SC-held operational holdings comprise 6.02%, but more than 85% are unviable.

(In majority of Punjab’s districts, SCs form one third or more of the populace, including SBS Nagar (42.51%), Muktsar (42.31%), Firozpur (42.17%), Jalandhar (38.95%), Faridkot (38.92%), Moga (36.50%), Hoshiarpur (35.14%), Kapurthala (33.94%), Tarn Taran (33.71%), Mansa (33.63%), Bathinda(32.44%), Barnala (32.24%) and Fatehgarh Sahib (32.07%).)

Of the total 12,168 inhabited villages, 4,799 villages were recorded as having SC population of 40% or more, including 57 villages with 100% SC population. In the last few decades, not a single government scheme has even been announced for the singularly SC villages.

Data from the 70th round of Land and Livestock Holdings Survey of the NSSO showed that 58.4% of rural Dalit households are landless and 71% of SC ‘farmers’ are agricultural labourers. They are clearly a disempowered demographic segment. A survey sourced from the book, “Untouchability in Rural India,” authored by Ghanshyam Shah, Harsh Mander, Sukhadeo Thorat, Satish Deshpande and Amita Baviskar (SAGE, New Delhi, 2006), showed that a quarter of the Dalits do not even enter police stations or ration shops, 33% of the public health workers refuse to visit Dalit homes, and 23.5% Dalits still do not get letters delivered to their homes. In nearly 14.4% of Indian villages, Dalits are not permitted even to enter the panchayat building and in 48.4% of villages, Dalits are still denied access to common water sources. In 35.8% villages, they are denied entry into village shops and in 73% of villages, they are not permitted to enter non-Dalit homes. In 70% of villages, non-Dalits do not eat together with Dalits. Punjab’s Dalits are just relatively better in terms of any pronounced social discrimination, a factor largely attributed to the influence of Sikhism that abhors caste. It remains an incontrovertible fact that the caste, nevertheless, prevails in the Sikh community and the state. Any intercaste marriages across the Mason-Dixon Dalit-upper caste lines are more of an aberration. Discrimination is the subtext of a Dalit’s life.

In such a scenario, the legal provision under which one-third of the cultivable shamlat land has to be reserved for auction in which only Dalits can participate was being observed mostly in the breach. Powerful landlords often put up proxy dalits, then pay them off with a pittance and cultivate the land themselves. A strong and aggressive grassroots movement to stress the Dalits’ legal right to one-third of the cultivable Village Commons has seen clashes, bloodletting, arrests, and a tense atmosphere in many villages of Punjab.

“A quarter of the Dalits do not even enter police stations or ration shops, 33% of the public health workers refuse to visit Dalit homes, and 23.5% Dalits still do not get letters delivered to their homes. In nearly 14.4% of Indian villages, Dalits are not permitted even to enter the panchayat building and in 48.4% of villages, Dalits are still denied access to common water sources. In 35.8% villages, they are denied entry into village shops and in 73% of villages, they are not permitted to enter non-Dalit homes.”

The struggle is understandable. Experts estimate the total cultivable Shamlat land in villages at around 1.57 lakh acres, of which about 53,000 acres should be the Dalits’ share. A number of farmer and agricultural labourer unions are now involved in fighting for this share, among these being the Punjab Khet Mazdoor Union (led by Zora Singh Nasrali and Lachman Singh Sewewala), Krantikari Pendu Mazdoor Union (headed by Sanjeev Mintoo, largely active in Sangrur, Barnala and Mansa), Dehati Mazdoor Sabha (led by Gurnam Singh and Mahipal, and largely active in Doaba and Majha), the Zameen Prapti Sangharsh Committee (ZPSC, headed by Mukesh Malaud and Gurmukh Singh, is the most active of these and has achieved some results in Sangrur and Patiala), the Pendu Mazdoor Union (led by Tarsem Peter, active in Doaba since 1991), and the Mazdoor Mukti Morcha (led by Bhagwant Samao’n). The list is by no means exhaustive.

At certain places, the struggle is sounding bugles of a complete rebellion. For example, in Sangrur’s Malerkotla tehsil, 225 members of gram sabha of Tolewal village passed a resolution on June 8, 2019 to lease out 25 bigha (5.25 acres) of village’s panchayat land to Dalits at a nominal annual rate of Rs 500/acre for 33 years. The 225 comprised more than 20 per cent of the 870 gram sabha votes. While there is no provision in law for leasing out the land for 33 years, the rebellious action galvanized the Dalit activists. Since then, while the Panchayat department did not accept the resolution, multiple attempts by the government to auction the land ended in fracas, disputes or failures.

Discrimination is the subtext of a Dalit’s life.

Ironically, far from selling off the Shamlat land to industrialists, Amarinder Singh government had earlier the same year announced its intention of actually buying land to give to Dalits for constructing houses.

In January 2019, the CM had announced allotment of one lakh plots of 1,360 square feet each to homeless Dalit families in the state. He had also announced that these five marla (one marla=272 sq ft) plots would be allotted to homeless scheduled caste families in each village, and where land is not available with the village panchayat, the state government will arrange the land. This was in keeping with the Congress’ poll manifesto. The law, in fact, provides for giving such plots to landless, homeless people without consideration of caste.

In reality, Amarinder Singh has been long fixated upon the idea of getting land from the farmers, giving it to industrialists and then facing serious resistance to his plans. In 2006, during his first tenure as chief minister, Amarinder Singh had come up with his favoured Farm to Fork project that saw the acquisition of 100 acres of land for industrialists in Ludhiana’s Nasrali, 42 acres in Dhoorkot in Barnala, 35 acres in Sunetta in Mohali, and several other land parcels. The 150-acre Ladowal farm was also given on a 30-year lease at a pittance of Rs 16,000 per acre annual lease. None of those projects fructified, and a lot of lands went into the industrialists’ kitty.

When it comes to resources, the Punjab government has little room left for development. Most welfare schemes have already come to a grinding halt. The non-tax revenue collection is down. Of the estimated Rs 9,477 crore non-tax revenue, the state has only collected Rs 1,325 cr so far. Tax revenues remain far below the target. Punjab has been complaining about and struggling to get the Centre to pay up about Rs 4,100 crore as GST compensation. State Finance Minister Manpreet Singh Badal had admitted in his February 2019 budget speech that Punjab’s total debt is expected to rise in 2019-20 to Rs 2,29,612 crore, thus effectively landing it in a debt trap.

Punjab, with just 1.54 per cent of the country’s geographical area, has come a long way since the days of the Green Revolution.

* * *

POLITICALLY, with its latest legislative surgical strike to snatch people’s wealth and hand it over to his industrialist honcho friends, much like the Congress’ Ambani-Adani jibe, the Amarinder Singh government is effectively upending the only credible victory that Rahul Gandhi ever scored against Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

It was Amarinder Singh’s leader Rahul Gandhi who led from the front the fight against a new and big business-friendly version of the Land Acquisition Act.

Rahul Gandhi’s party and mother, Congress and Sonia Gandhi, take much pride in the Manmohan Singh government’s version of the Land Acquisition Act, and had put up a spirited fight against the Narendra Modi government’s move to pass a more regressive version of that when it came to power in 2014, decimating the Congress.

Called the “Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, (LARR),” this United Progressive Alliance (UPA) legislation dealt with the controversial and highly emotive issue that had huge political implications and replaced a colonial-era law of 1894.

It was important to get it right since the law followed some of the most intractable struggles and people’s movements that independent India saw, including large-scale protests against projects like the Sardar Sarovar dam in Gujarat; a special economic zone in Nandigram and a Tata Motors plant in Singur (both in West Bengal) as well as Vedanta’s bauxite mining plans in Niyamgiri and Posco’s steel project in Jagatsinghpur (both in Odisha).

Among the Indian state’s biggest sins has been a merciless approach towards land acquisition in the name of development, be it public sector resources or private industry. This new legislation, considered a marked improvement over the colonial-era law, came into effect just five months before Narendra Modi burst on the Indian political scene with a decisive mandate after more than three decades of fractured electoral verdicts.

Gandhi was clear that self-reliant villages form a sound basis for a just, equitable and non-violent order. He held that the nation can be rebuilt only by rebuilding its villages, as evidenced by his work at Champaran (1917), Sevagram (1920) and Wardha (1938). In the years to come, he visualised an even more elaborate programme of constructive work that was based upon a decentralized political system with self-reliant villages.

Amarinder Singh’s and Rahul Gandhi’s party considers the LARR as among the most important laws passed during the ten years of UPA rule (2004 to 2014), helmed by a turbaned Punjabi, along with the Right to Information Act, Forest Rights Act and the National Food Security Act.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

The key aspects in which the UPA Act differed from the 1894 law were compensation, consent, social impact assessment (SIA) and rehabilitation & resettlement. It mandated compensation up to twice the market value in rural areas, equivalent to market value in urban areas plus an additional 100% solatium, calculated on the compensation paid for the land, unlike 30% in the old law. So, effectively, it entitled the landowners get, up to four times the market value in villages and twice the market value in cities.

Under the Land Acquisition Act passed by the UPA, which is still the law of the land since the Modi-I regime had to back off from its plan to ram through a much harsher law, all public-private partnership projects need consent of 70% of affected families while private projects need 80% of the affected families to give consent. While government projects do not need consent, it is not a fact Congress is proud of.

Jairam Ramesh, who was India’s Minister for Rural Development when the Bill was passed by the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha between August 29 and September 5, 2013, terms the exemption given to government projects from consent as “a compromise I had to make to get the bill passed.”

“Ideally, consent should be required even for government projects,” Ramesh has since maintained. His book, “Legislating for Justice: The Making of the 2013 Land Acquisition Law,” co-authored with Muhammad Ali Khan, is a testament to the thought process and the struggle that went through in pushing this bill through the Parliament.

It is this legacy of the Manmohan Singh government, Sonia Gandhi’s leadership and Rahul Gandhi’s bragging rights that Amarinder Singh is out to destroy with his push for legislation to enable the industrialists, entrepreneurs, speculators to acquire shamlat land that has vested in panchayats for hundreds of years.

Quoting Gandhi to Punjabis is a little out of fashion, but try this: “We are inheritors of a rural civilization… To uproot it and substitute for it an urban civilization seems to me an impossibility.” (Young India, November 7, 1929; 42:108.) Neo-Gandhian Congressman Amarinder Singh, a royal who is loathe to be seen in khadi, is making it possible. Captain hai to mumkin hai!

A lot is possible with this Captain of the Congress in Punjab. He demanded a bravery medal for the army officer who trussed up a Kashmiri citizen on his jeep as a human shield against possible stone pelting, advocated a free hand for army in Kashmir, and demanded 10 heads of Pakistani soldiers in lieu of each Indian fauji killed on the border. On most burning issues dear to the Congress, Amarinder has stayed on mute mode, be it beef ban, love jihad, ghar wapsi, Ishrat Jahan encounter, assaults on JNU students, suicide of Rohit Vemula, Rafael, Verma-Asthana CBI squabbles, Rohingyas, lynchings, or even on the National Herald case in which all he could manage was a statement against Subramanian Swamy. When pushed into criticising the BJP, he manages to do so without naming Modi or Amit Shah. Since Amarinder Singh is clearly with the BJP line on matters of national security, now with his push to pull off the sale of village Shamlat lands, he has decisively moved towards the Right on the economic front, too. But for appearances’ sake, let us continue to call him a Congressman. As we said, Captain hai to mumkin hai.

It is this legacy of the Manmohan Singh government, Sonia Gandhi’s leadership and Rahul Gandhi’s bragging rights that Amarinder Singh is out to destroy with his push for a legislation to enable the industrialists, entrepreneurs, speculators to acquire shamlat land that has vested in panchayats for hundreds of years.

Though not everyone agrees it will be mumkin for him to pull off this one.

“The Shamlat land is a social security of the village. Villages are resource-crunched, and in many cases, the Village Commons are either the sole or the most significant source of income for the panchayat. As things stand, the state governments have already pulled out from allocating even minimal resources to local bodies. If the panchayats are made to sell shamlat land, it will be the end of villages as we have known them for centuries,” said Balbir Singh Rajewal, president of the Bharti Kisan Union (BKU).

Hamir Singh, a senior journalist with a deep understanding of the grassroots functioning of villages, rural economy, resources available to panchayats and the functioning of this third tier of democracy, said the latest move of making/enabling panchayats to sell off the Village Commons was part of a pattern of pauperisation of villages.

“The political leadership of Punjab, across party lines, is no more invested in the idea of a village. Not even a third rung leader of any political party actually lives in his village. Anyone with a secure job has already shunned the village. Those who still live in villages actually live in their palatial farmhouses, effectively having insulated themselves from the village economy and social life. Every politician, and almost every economist, is sold on the idea that the village is an unsustainable entity in modern civilisation, that migration from the village to the city is inevitable, that agriculture has to yield to industrialisation, and gradually we will all live in urban habitations and our food can be produced by a fraction of those who are still involved in cultivation. It is a narrative bought lock, stock and barrel and shows the bankruptcy of imagination and little understanding of what this huge mass of people will eventually do,” Hamir Singh said.

It is exactly such an approach that has made it possible for the Amarinder Singh regime to not even face a question as simple as why he is going to tear the reputation of Manmohan Singh, Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and all of 2004-2014 UPA to smithereens.

Amarinder Singh’s legislation, which will make it possible, and will facilitate, the takeover of shamlat land of villages by private land sharks, does not have any provision for obtaining the consent of even 10 per cent of the families affected. In fact, every single family in the village could be against it, but if the panchayat wants to, it can sell the land.

It does not guarantee proper compensation, does not have a fair remuneration formula, does even broach the idea of compensation for those dependent upon the shamlat land, has no provision of a social audit and impact assessment (SIA) and does not offer anything else in return except for money, the amount of which is to be decided without consulting the village.

It also negates every single spirit of the Panchayati Raj Act pushed by Rajiv Gandhi and tom-tommed by Sonia and Rahul Gandhi as it cares two hoots for the idea of a Gram Sabha. In his assessment cum review of twenty years’ worth of functioning of the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), Mani Shankar Aiyar, former Union Minister for Panchayati Raj and someone who worked closely with Rajiv Gandhi and was a virtual mid-wife for ushering in this remarkable piece of legislation lamented that the Panchayati raj was to become a system of administration through the institution of Gram Sabha, but has merely become rule through gram panchayat. In fact, he acknowledged that on the ground, it has been reduced to rule by sarpanch.

“The worst consequence … is the distortion of Panchayat Raj…into ‘Sarpanch Raj’, that is, the reduction of Panchayat Raj Institutions to a nefarious nexus between the President of the Panchayat at the village/intermediate and district levels, on the one hand, and elements of the bureaucracy, on the other, that have made Panchayat Raj synonymous with the decentralization of corruption. This, in turn, has led to enormous expenditure on Panchayat elections as the means to securing even greater returns by milking the Panchayat Raj system,” Aiyar wrote in his 2013 report (Vol 1, page 37, Para 2.41 of Towards Holistic Panchayati Raj – Twentieth Anniversary Report of the Expert Committee on Leveraging Panchayats For Efficient Delivery of Public Goods and Services).

Ignoring the Panchayati Raj Institutional framework, pummelling the safeguards his party conceived and fought for in its Land Acquisition Act, Amarinder Singh has kept the Gram Sabha, a body comprising all the bonafide voters of the village/panchayat, completely out of a crucial and life/lifestyle-changing decision-making about the common wealth of the village collective.

And yet, the opposition parties, including the Akali Dal and the Aam Aadmi Party have raised extremely feeble voices against the move.

“The worst consequence … is the distortion of Panchayat Raj…into ‘Sarpanch Raj’, that is, the reduction of Panchayat Raj Institutions to a nefarious nexus between the President of the Panchayat at the village/intermediate and district levels, on the one hand, and elements of the bureaucracy, on the other, that have made Panchayat Raj synonymous with the decentralization of corruption. This, in turn, has led to enormous expenditure on Panchayat elections as the means to securing even greater returns by milking the Panchayat Raj system,”

It is also a surprise that neither the religious demographic, including the SGPC or Sikh, Hindu, Muslim religious bodies, nor the environmentalists have picked up the gauntlet and challenged the Amarinder government. Tax-payer funded institutions such as the Punjab State Institute of Rural Development (SIRD), the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (CRRID) or the National Institute of Rural Development & Panchayati Raj (NIRD&PR) have not lifted a finger on the issue or made their opinion known.

Amarinder Singh government has singularly failed on the Panchayati Raj front, and the idea of Gram Sabha, ostensibly dearest to the Congress at the national level, is alien to Punjab, thanks to the politicians’ proclivity to keep a vice-like grip on villages and villagers. These same villages could have been a source of new leadership. After all, 1.27 crore voters in Punjab’s countryside elect almost 13,000 sarpanches and 83,831 panches. With 85,000 wards, 145 panchayat samitis with 2,750 members, 22 Zila Parishads and 350 Zila Parishad constituencies, the state effectively elects one lakh directly elected representatives, some 50,000 of them women. Imagine the resource pool for politics that Punjab could have created if the government had let a better version of democracy prevail at the village level!

The fact is that the Panchayats have become a new till for the politicians to loot. Under the 14th Finance Commission, Panchayats were provided money directly. Across India, they received Rs 2,00,292 crore in five years, that comes to around Rs 15 lakh annually for each panchayat with big ones getting up to Rs 1 crore. The entire exercise was predicated on the Gram Sabha taking a lead, the panchayat being merely the executing agency to fulfil the wishes of the Gram Sabha. A fixed number of periodic meetings of the Gram Sabha are mandatory under the 73rd Constitutional Amendment.

GRAM SABHA enjoys immense power under the law. It can conduct a social audit of all development work, and the concerned authorities are bound to facilitate it. The basic philosophy was that the villagers should think, decide and act for and in their own collective socio-economic interests. While a Gram Sabha enhances people’s participation in the decision-making processes, it also avoids the pitfalls that a Panchayat can fall into, and thus effectively deals with the sad social reality of a stark power imbalance where the marginalized know the least. It underlines the principle that collectively, they are a force.

In simple terms, the Gram Sabha is the Corporate Body while the Panchayat is the Executive Body, or in other words, Gram Sabha is a legislature while Panchayat is a Cabinet. Besides, a Gram Sabha can overrule a Panchayat and re-direct it. It also deals with intransigent sarpanches or panchayats since it is empowered to call a meeting even if the sarpanch refuses to convene one. All it requires is for 20 per cent of the voters to sign and give notice of 15 days. This is Direct Democracy 101.

For every government benefit scheme, the law empowers the Gram Sabha to draw up a list of beneficiaries. Only if it fails to do so, the panchayat is to take over that task. In practice, it is a local political tough who dispenses favours. Politicians of all hues in Punjab are guilty of killing the spirit of panchayati raj.

And this is the spirit that the Amarinder Singh Government, too, first completely negated, and is now adamant on disempowering and disenfranchising the rural populace by enabling and empowering panchayats to sell off the centuries-old social security deposit of the villages to private industrial and land sharks for a pittance and then giving them deferred payment options.

GRAM SABHA enjoys immense power under the law. It can conduct a social audit of all development work, and the concerned authorities are bound to facilitate it. The basic philosophy was that the villagers should think, decide and act for and in their own collective socio-economic interests.

To just give you an idea of how harebrained the new law is, it actually mentions that a Panchayat can sell off the shamlat land in the village to an industrial house which is not even required to make the full payment but can pay just one-fourth upfront, the rest taking years to be realised, and then, using that money, the panchayat can go and buy land elsewhere if it needs it.

So a panchayat in Mansa in Punjab’s deep south can sell off its shamlat land, but since the Dalit women need it to make dung-cakes and the local landless labourer needed five marlas to construct a house, the new law empowers the panchayat to buy land in Gurdaspur, give five marlas to the needy guy and ask the dalit woman of Mansa to go make dung-cakes in Gurdaspur!

It is astounding as to how valuable land could be in Punjab and to what fruitful uses it could have been put to. Coupled with the provisions of the MGNREGA, an all-empowered Gram Sabha can put the Shamlat land to many imaginative uses, ensuring a constant income stream for villagers.

Theoretically, the Gram Sabhas in Punjab can move Resolutions against any plans to sell off the family jewels of the village, but in practice, the institution has been destroyed. A spirited band of political activists working under the banner of International Democratic Party (IDP) has been fighting hard for years now to push the cause of Gram Sabha, trying to set up networks of aware villagers, educate activists, disseminate an understanding about the Gram Sabha’s powers and inspiring people to hold Gram Sabhas, but no mainstream political party has come even close to touching the agenda with a barge pole.

* * *

THE STORY OF the Punjab’s elite gobbling up the Village Commons with a monstrous hunger is now the stuff of legends. The village common lands around Chandigarh were encroached upon with so much impunity that it took a Tribunal appointed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court under the leadership of a retired judge of the Supreme Court to dig out facts so shocking that one is inclined to suspend all sense of belief.

The explosive revelations about landgrab of Shamlat land in the Punjab villages around the periphery of Chandigarh are closely linked to the aforesaid order of the Supreme Court in the Jagpal Singh case. The Village Commons loot scandal came to light when, in 2007, a Nayagaon resident, Kuldip Singh, filed a writ petition in the Punjab and Haryana High Court against VIPs’ land loot (CRM No. 23125 of 2011).

Once it became apparent how public property belonging to Gram Panchayats, in and around the periphery of Chandigarh and in the Mohali District (created in Punjab in 2006), called Sahibzada Ajit Singh (S.A.S.) Nagar, were sold, the HC asked the Deputy Commissioner, S.A.S. Nagar, to file a detailed affidavit by 30 March 2012, giving the steps he proposed to take against the vendors, the vendees, the person who allowed registration of the sale deeds and the Gram Panchayats who did not raise any plea with respect to their title.

The explosive revelations about landgrab of Shamlat land in the Punjab villages around the periphery of Chandigarh are closely linked to the aforesaid order of the Supreme Court in the Jagpal Singh case.

Affidavits (filed in April and May 2012) of about 60 influential persons along with that of the then Chief Secretary convinced the judges that the matter required to be probed by an independent tribunal which should be presided over by an eminent judge of either Supreme Court or from this Court. It had by then become clear that top bureaucrats, police officials and top political leaders were among beneficiaries as government officials were permitting the sale of public property, i.e. shamlat or common land, in rural areas/adjacent cities. The Court emphasised (with reference to Rule 16 (ii) of the East Punjab Holdings (Consolidation and Prevention of Fragmentation) Rules, 1949) that though ownership of such land vests in proprietors, its management and control lies with the Gram Panchayat. These panchayats, whose family jewels were being looted, had no problem with the state of affairs.

Once the Tribunal was set up on May 29, 2012, under retired Supreme Court judge, Justice Kuldip Singh, to investigate this scam worth hundreds of crores, the State itself retaliated, arguing that the High Court had no right to set up the Tribunal.

Chronicling and investigating the Shamlat land grab in villages around Chandigarh, such as Nada, Karoran and Bartana in the periphery of the capital, the Justice Kuldip Singh Tribunal found record mutations done in connivance with revenue and panchayat officers and was compelled to name top politicians, police officers and bureaucrats as having grabbed shamlat land of panchayats.

The Tribunal submitted its report on March 13, 2013, which had details of 23,082 acres of shamlat and 653 acres of Jumla Malkana land encroached just in Mohali. At the time, the retired judge of the Supreme Court put the conservative market price figure for this encroached Shamlat land at Rs 25,000 crore. The Punjab Government of Captain Amarinder Singh set up a sub-committee of the Cabinet, headed by the then Local Bodies Minister Navjot Singh Sidhu, Rural Development and Panchayat Minister Tript Rajinder Singh Bajwa and Revenue Minister Sukhbinder Singh Sarkaria, to study the report. Sidhu, later eased out from the Cabinet, went on to say that the value of land grabbed in Mohali alone exceeded the entire debt burden of Punjab, nearly Rs 2 lakh crore.

A former Director-General of Police, Chandra Shekhar, who probed land grab in Chandigarh UT’s periphery, submitted 12 reports after examining revenue records and found nearly 25,000 acres illegally occupied in Mohali district alone. Those who have tracked the development claim that an estimated five to six lakh acres of government land is under illegal occupation throughout Punjab.

The Tribunal had also recommended a CBI or similar probe into “land grab cases” involving public lands in Punjab villages around Chandigarh and setting up of a Special Bench to follow up on the Tribunal’s work. It also pushed for special officers to deal with land matters and not leave the work of protecting Panchayat/Government/Public lands to governmental authorities. The Tribunal also wanted to re-open and decide afresh the orders of the Civil Courts/Consolidation and Revenue Authorities which were prima facie illegal and based on fraud/collusion and conspiracy. It also wanted the High Court to invoke suo moto powers for the cleanup act, and recommended punishment for Revenue/Consolidation Department officials found involved. It also recommended abolition of the institution of patwaris/kanungos, calling them highly corrupt. Most importantly, it asked for a regular audit of the Shamlat lands.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

Since then, the matter has only been lingering in red tape. Captain Amarinder Singh has never broached the subject on his own, and the opposition Akali Dal has never troubled him on the issue of loot of the Village Commons. The Aam Aadmi Party is basically an electoral machine and the moral compass of its Delhi-based leadership is a bit tricky when it comes to Punjab issues. It once chucked out its state president citing a video of an act of moral turpitude, but years later, no one has ever seen the video and it is difficult to find a single soul who believes it ever existed.

* * *

Family jewels are most important to families that are pushed towards pauperisation. How impoverished are Punjab’s villages can be guaged from the Government of India’s Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) data that puts the number of rural households with at least one salaried job at just 12.82 per cent, with 56.56 per cent rural households surviving on a monthly gross income of less than Rs 5,000. Only less than 18 per cent rural households have an income of Rs 10,000 or more, and 64.51 per cent households own zero land. Half the rural households, 48.84 per cent, have no motorised means of transport (two wheeler, car, tractor etc). When, as per the same SECC data, only 3.02 per cent of the rural households in Punjab have a member who is a qualified graduate or above, and with the Census data showing literacy rate among SCs as 64.81% (compared to Punjab’s 75.84% and India’s 73.00%) with female literacy rate at 58.39%, where do you think the educated, engaged resistance was to come from to government policies that are squeezing the life out of Punjab’s villages?

Perhaps the Dalits should have come out in huge numbers to hold protests, storm the social media or inundate the state with creative posters, as you saw in the ongoing anti-CAA-NRC agitation, but with almost all of them being either agricultural labourers or stuck in low wage, arduous occupations, a dharna becomes a luxury, a day at Chandigarh’s Sector 17 plaza means loss of income, sometimes even a loss of three meals. Life at the margins is a little hard, you know.

Family jewels are most important to families that are pushed towards pauperisation.

Since the landless agricultural labourers are a major stakeholder in the shamlat land, thanks to the way the life of Punjab villages has evolved as well as the law that gives the Dalits among them the exclusive rights to cultivate one-third of the cultivable land, one wonders if the Amarinder Singh government, sworn to improve their living conditions, paid heed to the latest research about their socio-economic conditions.

The first-ever survey about farm indebtedness in Punjab that covered agricultural labourers, unlike earlier studies that left out farm labour, showed that more than 80% of the state’s agriculture labour families are under debt. Entitled “Indebtedness Among Farmers and Agricultural Labourers,” the survey by renowned economist, Prof Gian Singh of Punjabi University, Patiala and his associates Dr Anupama, Dr Rupinder Kaur, Dr Sukhvir Kaur (all from Department of Economics at Punjabi University) and Dr Gurinder Kaur, a professor at the Department of Geography at the same university, depicted a shocking skew in incomes, expenditure and consumption patterns of farm labourers. Large landholding farmers spend more than six times than marginal farmers and more than 12 times than agricultural labourers on durables, non-durables, services and socio-religious ceremonies.

While average annual income of a farmer family is Rs 2.92 lakh – ranging from Rs 12.03 lakh for large farm-size owner farmer’s family to Rs 1.39 lakh for marginal farmer’s family – an average agriculture labourer’s family earns a mere Rs 81,452 in a year, with more than 90 per cent of it coming from hiring out labour in agriculture.

The survey underlined the pitiable state of farm labourers, a section hitherto ignored by many farm economists. Juxtaposed with the fact that the much-talked about farm debt waiver of the Amarinder Singh government completely left out the landless agriculture labourers, it betrayed a mindset that is again confirmed by the latest move to sell off shamlat lands, in many cases the only means of survival of this impoverished lot.

Cleverly and deliberately, Amarinder Singh has made a major push for this legislation when no one is looking. The country is embroiled in a fast-paced news cycle about the Citizenship Amendment Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens, the headlines are being claimed by the blood spilling in university campuses, and Punjab is devoid of any real opposition as Akali Dal struggles to keep its flock together and the AAP waits in the wings to see when can it actually come into the electoral picture.

The very first attempt to sell off the Village Commons is going to be made in Rajpura in the Chief Minister’s home district of Patiala. The Punjab government plans to give away almost 1,000 acres of Village Common Land to industrial investors. Incidentally, the previous state government had also floated a similar idea to lease panchayat lands to industry, but now the Amarinder Singh government wants to outrightly sell it.

And this is not a stand-alone move to push the marginalised over the brink and sound the death knell of the idea of the village as we have known it so far. Coming up next are amendments in the Factories Act, the Industrial Disputes Act and the Contract Labour Act, all ostensibly aimed at boosting employment and industrial development, and in practice aimed at disempowering labourers’ right to unionise, and making them vulnerable to whims and fancies of exploitative practices.

Alongside the Amarinder Singh government’s push to “gift” shamlat lands to MSMEs, it has also made it easier for them to indulge in exploitative practices without facing regulatory compliance. The Punjab Government officially stated last month (December 2019) that it wanted “to reduce the regulatory compliance burden by waiving the requirement of certain approvals and inspections for establishment and operations for MSMEs.” Mere self-declaration would henceforth be enough, it said. Punjab currently has approximately 2 lakh MSME units.

Ostensibly preparing for its Rural Industrial Revolution, the Amarinder Singh government also weakened the Factories Act, 1948, Industrial Disputes Act 1947 and Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970. Inserting certain amendments and a new section 106 B in the Factories Act, 1948, it increases the threshold limit of number of workers from ‘ten’ and ‘twenty’ to ‘twenty’ and ‘forty’, in factories with manufacturing processes carried out with or without the aid of power, respectively. The new tweaks also allowed for compounding of offences. So eager was Amarinder Singh to see this that his Cabinet gave its nod to do all this through an ordinance.

The Cabinet has also approved amendment to Section 25K (1) to increase the minimum number of workers for applying the provisions relating to layoffs, retrenchment and closure to 300 from 100, while shrinking the limitation period to just three months. The government is also amending the Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970, jacking up the ambit of the Act from present threshold limit of 20 to 50 workers.

And these MSMEs are coming soon, to a village next to you.

The very first attempt to sell off the Village Commons is going to be made in Rajpura in the Chief Minister’s home district of Patiala. The Punjab government plans to give away almost 1,000 acres of Village Common Land to industrial investors. Incidentally, the previous state government had also floated a similar idea to lease panchayat lands to industry, but now the Amarinder Singh government wants to outrightly sell it. Intermittent reports have already started trickling in about a strong local-level resistance to the move. In the past, Punjab saw a strong anti-land acquisition struggle in Barnala (against the Trident industry group) and in Mansa (against Indiabulls Power firm).

Unlike the “Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013,” which has a provision that if any land acquired from farmers is not used for the stated purpose, then it can be vested back to the original land owners, the new provisions backed by the Amarinder Singh government have no such clause.

Common property resources, which constitute 15 per cent of the country’s total area, are shrinking at a rate of 1.9 per cent every five years due to encroachment, as per the National Sample Survey Organisation. Since Independence, more than 834,000 hectares of village commons have been encroached. Village commons include everything from pastures, forests and common threshing grounds to ponds, irrigation channels and rivers, and play an important role in rural economy.

The Punjab Village Common Lands (Regulation) Act, 1961 nowhere provides that the state government can legislate a law enabling panchayats to sell land to industrialists to set up MSMEs in villages, said Dr Pyara Lal Garg, a widely-respected social and political activist and former Registrar of Punjab’s Baba Farid University of Health Sciences.

“Punjab government has not explained how any village panchayat can sell something that does not belong to it, or that never belonged to it? Shamlat land, by its very definition, is land in collective possession of the residents of a village,” said Dr Garg.

Common property resources, which constitute 15 per cent of the country’s total area, are shrinking at a rate of 1.9 per cent every five years due to encroachment, as per the National Sample Survey Organisation. Since Independence, more than 834,000 hectares of village commons have been encroached.

Villages have had common land resources for centuries that remained secure simply because no one ever had the real power to sell them off wholesale. The Shamlat land existing in Punjab’s villages today includes land variously described as ‘Jumla Malkan Wa Digar Haqdaran Arazi Hassab Rasad’, ‘Jumla Malkan’, ‘Mushtarka Malkan’, ‘banjar qadim’ etc lands which were reserved for the common purposes of a village under Section 18 of the East Punjab Holdings (Consolidation and Prevention of Fragmentation) Act, 1948. [See 2(g)(6) of Act of 1961].

Gram Panchayat can decide usage, maintain, or even make a decision to lease or sell but how will do so without evolving a mechanism or rules for ascertaining consent is not clear. Non-consensual sale of shamlat land by Panchayat will be violative of Article 31-A of the Constitution of India.

The NSSO survey says 45 per cent of the rural households depend upon the Village Commons for firewood collection, 13 per cent for fodder collection, 20 per cent for grazing land, 30 per cent for water for livestock and 23 per cent for water for irrigation. As for the rural SC population, they are almost entirely dependent on these Village Commons for all such needs.

“Punjab government has not explained how any village panchayat can sell something that does not belong to it, or that never belonged to it? Shamlat land, by its very definition, is land in collective possession of the residents of a village,”

“The loss of Shamlat land will actually be a much bigger loss,” said Dr Garg, adding, “Most village infrastructure has been built on land parcels given from the Shamlat lands, be these panchayat ghars, schools, dispensaries, anganwadis, janj ghars, cremation grounds or grazing lands. Village festivals are normally held on these Village Commons, as are women festivals such as Teeyan Da Mela. Sale of shamlat land will mean non-availability of land for upgradation of schools, or expansion of any existing structure. It will also mean the end of social life as villages have known for centuries.”

Even without powers to sell off land, Shamlat lands have been heavily encroached, ponds have been filled, sold and lost forever. With these powers to sell common land, how many dry ponds will survive? How many grounds will not be sold because the panchayat will decide that it is most necessary for the village mela?

It is true that states across India have been skimping on consent, social impact assessments and rehabilitation and resettlement but the Amarinder Singh government is guilty of letting the bar plummet to levels unprecedentedly low in centuries.

Of Punjab’s 5.03 million hectares geographical area, 4.20 million hectares, or 83%, is under cultivation, with cropping intensity pegged at almost 190% or above. Imagine the kind of pressure the industry sector will bring upon the panchayats to sell off their lands!

Veteran journalist Tarlochan Singh, who has chronicled for years the saga of those villages whose land was acquired to set up the city called Chandigarh, said if the purpose was to set up industry and generate employment, there are a humongous number of units lying closed in town after town.

He is right. Thousands of MSMEs in Punjab have been reeling under heavy debt for years, crying hoarse for bailout packages, and RTI activists in 2015 found that 18,770 units had shut down or migrated out of Punjab since 2007, in addition to 6,550 industrial units that had been declared sick. Since then, things have moved further south. Alarming data spews out of every source, be it the Union Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises talking about Punjab units running in heavy losses, the Punjab Finance Corporation (PFC), the nodal agency for extending loans to industrial units, detailing units defaulting on loan repayment, or the Punjab Industry Department forever busy preparing bailout packages for sick industries.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

“Those whose lands were acquired for the so-called City Beautiful are still running from pillar to post to seek compensation. What makes you think those selling shamlat lands will be able to recover costs?”

New law has provision that industrialist will pay 75% of cost of land to panchayat in four annual instalments. “How many panchayats will be able to afford the litigation to drag the industrial houses to court if they do not pay one or more instalments? If the PSIEC will stand guarantee, what is the guarantee that tomorrow, the PSIEC will not become a sick PSU itself?” asks Dr Garg.

Tarlochan Singh, whose book, “Chandigarh: Ujjaadiyan Di Dastaan” (The Saga of the Displaced), said, “Those whose lands were acquired for the so-called City Beautiful are still running from pillar to post to seek compensation. What makes you think those selling shamlat lands will be able to recover costs?” A more significant question is if there ever can be compensation for centuries of way of life.

In his remarkable book, “The Price of Land: Acquisition, Conflict, Consequence,” Sanjoy Chakravorty, professor of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia, says land should not be acquired through government writ at all but should instead be bought through negotiations like in a free market.

It is a view with which Jairam Ramesh, a fellow Congressman of Amarinder Singh, concurs in his book. “Land acquisition should be under the rarest of rare circumstances. In fact, over a 10-15-year period, we should move to a situation where governments do not acquire land even for their own use. They should buy.”

When seen in the context that contemporary India has seen the most violent of people’s movements on the issue of land acquisition for industry or infrastructure, be these in Singur, Nandigram, Niyamgiri or Maha Mumbai, this simple market truth makes sense. If the industry needs it, it should go and buy at market rates. The counter-argument that land acquisition is an obstacle in India’s growth path is a spin put out by chambers and apologists of big business. At the end of the day, the issue of land is primarily a political issue. Your view hinges on your politics. Captain Amarinder Singh is making his politics, priorities and proclivities clear with his latest legislative move. That his politics, priorities or proclivities are not very different from the other claimants to power in Punjab should be no reason why questions should not be raised.

“Land should not be acquired through government writ at all but should instead be bought through negotiations like in a free market.”

Amarinder Singh could have used the Supreme Court judgement in Rohar Jagir village in his backyard to retrieve his people’s common land that was robbed on the strength of money and muscle power, but instead, he is now finding legal ways of taking away that land from the villages. (Of course, the Supreme Court judgement could also be used to evict the poor from shamlat lands. A case in point is the evacuation of the poor from the Yamuna riverbed in Delhi and instead using that land for setting up the Commonwealth Games Village at the same site.)

“Given Punjab’s realities, one would imagine that the central political question would have been of land reforms, of clarifying land records, of identifying land possessions in breach of the land ceiling act. Instead, the government is denying the share of dalits in Shamlat land and is now out to altogether sell the shamlat land,” said Paramjit Kaur Longowal, a senior activist of the Zameen Prapti Sangharsh Committee (ZPSC), adding that this will only widen the scope of their movement.

Thanks to the stagnation in the agriculture sector, farmer organisations’ view is more informed by the economics of land prices than by the principle of securing family jewels. While dalit and agriculture labourers are strongly opposing the government’s move to sell shamlat land to industries, the far more resourceful farmer organisations have been deploying language that betrays either confusion or plausible flexibility. While the faction led by Balbir Singh Rajewal has clearly opposed the move and Rajewal has said the government will get to know the real extent of the opposition once its bureaucrats and officials reach the villages to demarcate the Village Commons, the BKU (Ekta Ugrahan) faction did oppose but kept enough margin for nuancing.

“The decision will hit the landless and farm labourers hard,” Joginder Singh Ugrahan and Sukhdev Singh Kokri Kalan of the BKU (Ekta-Ugrahan) said in a statement, but also added, “The union is not opposed to setting up industry in rural areas and panchayats will be happy to give land for this purpose, but creating a land bank in advance will create problems as in many cases, there are fears that no industry will be set up and the land will be gobbled by speculators.”

Farmer organisations are more likely to protect the interests of landed farmers, and issues of landless or those dependent on land-owning farmers are secondary for them. With not just marginal or small farmers facing a bleak future, but even bigger farmers stuck in the sectoral crisis, selling land does not seem like such a bad idea.

The “Pind Bachao, Punjab Bachao,” an umbrella body of do-gooders that includes widely respected senior retired professionals, social and political activists, has strongly opposed the government’s move and has given a clarion call to the Gram Sabhas to pass resolutions and refuse to sell the Shamlat lands.

The issue of usage of shamlat land, its connection with ensuring food security and its role as sole source of sustenance for many is well understood by economists. Congressman Amarinder Singh may not be very keen to read scholars from a university his party is fighting for but Amit Bhaduri, Professor Emeritus of Jawaharlal Nehru University, in his foreword to the recent tome on “Food Security in India: Myth and Reality” by Vikas Bajpai and Anoop Saraya, writing about the issue of food security, said: “(The) question is not the high or low rate of economic growth, fiscal or current account deficit…but what needs to be done to not just pretend to alleviate poverty and hunger as an election gimmick but to demolish that evil structure that nurtures it in the name of democracy. Identifying that structure is the first step of a longer journey.” (During the writing of this story, Prof Bhaduri resigned from his position in the JNU in protest against the attack on students protesting against the Citizenship Act.)

It will be a no-brainer to ask of the Amarinder Singh government whether it is planning to sell the Shamlat land of Punjab’s villages to industrialists in the name of Rural Industrial Revolution to remove the structures that keep our villages impoverished and disempowered, or whether this will actually strengthen the structural claws which will snuff the life out of this civilisational entity called a village. My guess is that you know the answer. The question is what do you plan to do about it?

A senior lawyer who closely tracked the Rohar Jagir resident Jagpal Singh’s case, said without restoring and protecting the Village Commons, the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution of India, aligned with Mahatma Gandhi’s vision about gram swaraj, will have no meaning, including what is provided under the XI Schedule of the Constitution for the Panchayats to economically develop the villages and ensure social justice.

It will be a no-brainer to ask of the Amarinder Singh government whether it is planning to sell the Shamlat land of Punjab’s villages to industrialists in the name of Rural Industrial Revolution to remove the structures that keep our villages impoverished and disempowered, or whether this will actually strengthen the structural claws which will snuff the life out of this civilisational entity called a village. My guess is that you know the answer. The question is what do you plan to do about it?

The state of the villages can be gauged from the fact that the state government’s own surveys have pegged farmers’ and farm labourers’ suicides at over 16,000 in 15 years. The latest data released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) within days of Punjab Cabinet giving its approval to sell Shamlat land, showed that farm suicides are on a decline, but Amarinder government’s own data shows these are on the rise in Punjab. The NCRB has not shared Punjab data with the government, a fact admitted by KS Pannu, Secretary, Agriculture. The NCRB did not release data for farm suicides for 2017 and did not share statewise data for 2018, drawing widespread criticism but not one minister or MLA of ruling Congress is on record as having issued a single statement to condemn this action of Modi government.

ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੜੋ

Since we are currently watching India in the throes of a battle to save the Constitution, it will be appropriate to recall Article 39 (a), (b) & (c) of the Indian Constitution (Directive Principles of State Policy):

The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing

(a) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means to livelihood;

(b) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good;

(c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment;

Various apex court judgments have held that in Article 21 — “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law.” — ‘life’ does not mean merely the physical act of breathing, does not connote mere animal existence or continued drudgery through life but has a much wider meaning that includes right to live with human dignity, right to livelihood, right to health, right to pollution-free air, right to a meaningful, complete, and worth living life.

Whether or not the Congress government of Captain Amarinder Singh is working as per the diktats of the Constitution that his party’s presidents, both former and interim, are fighting to safeguard, is a question we leave you to answer. All we know is that Punjabis’ favourite slogan of ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ clearly means something very different to Amarinder Singh who is in a hurry to usher in this dangerous Rural Industrial Revolution. If you allow passage of a law to sell the Shamlat lands in villages to the industry, it will be the end of Punjab as you and your forefathers have always known. The time to put up a fight to save the land of the Gurus is now. Tomorrow will be too late. Choose your side in this battle.

A Revolution is coming anyway.

SP Singh is an independent journalist who has worked with leading national mastheads in the capitals of India and Punjab, has been tracking Punjab for close to twenty years now and is firmly plonked on the intersection of journalism and academia. He is also the host of one of Punjab’s longest-running news television debate shows, currently writes a weekly column for a leading Punjabi newspaper and unapologetically ploughs a lonely furrow. He lives in the termite hills beyond Chandigarh, brews his own coffee and stews in his own verbose world.