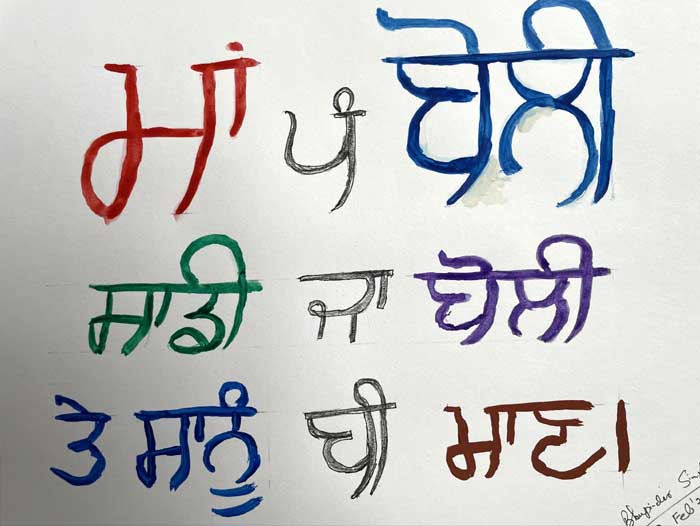

Punjabis can rejuvenate mother tongue Punjabi

Like everybody else, Punjabis across the world will celebrate with gusto International Mother Language Day on February 21. For the author, a reminder of the same struck much earlier when he read the news item about the Canadian Government agreeing to settle a class action claim “seeking reparations for the loss of language and culture brought on by Indian (First Nations indigenous peoples) residential schools, for $2.8 billion.” The author deeply pondered about the role of schools and colleges in his homeland Punjab and parts of India not caring about the use, role and status of his mother tongue Punjabi. This article flows out of his love and concern for his mother tongue even while living in the United States as he articulates steps for the rejuvenation of Punjabi.

![Like everybody else, Punjabis across the world will celebrate with gusto International Mother Language Day on February 21. For the author, a reminder of the same struck much earlier when he read the news item about the Canadian Government agreeing to settle a class action claim “seeking reparations for the loss of language and culture brought on by Indian (First Nations indigenous peoples) residential schools, for $2.8 billion.” The author deeply pondered about the role of schools and colleges in his […]](https://www.theworldsikhnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Punjabi-Language-360x235.jpg)

The language which is the mother tongue of over 130 million people is at risk as it is not being taught, spoken, or propagated the way it should be. The official apathy extends on either side of the border that divides Punjab. It is a pretty grim and alarming reality which should be a wake-up call for all of us who are in deep slumber.

We may claim pride in our heritage, but we shy from speaking Punjabi. We claim we are Punjabi by nature and food, but our spoken words do not reflect it. It will be no exaggeration to say that when it comes to our mother tongue, we have been carrying a self-perceived inferiority complex. In fact, Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) observed this trait in Punjabis over 500 years back, as reflected in this revelation,

ਘਰਿ ਘਰਿ ਮੀਆ ਸਭਨਾਂ ਜੀਆਂ ਬੋਲੀ ਅਵਰ ਤੁਮਾਰੀ ॥੬॥

Translation: In each and every home, everyone addresses using the term “Mian” for greetings; your language has changed, O people. ||6||

Guru Granth Sahib, Page 1191

The picture of the consequences of neglect as painted By Guru Nanak Ji is:

ਖਤ੍ਰੀਆ ਤ ਧਰਮੁ ਛੋਡਿਆ ਮਲੇਛ ਭਾਖਿਆ ਗਹੀ ॥

Translation: The protectors (Khatris) have abandoned their religion and have adopted a foreign language.

Guru Granth Sahib, page 662

That was the language of rulers then, but now it has been replaced by Hindi/Urdu and English instead. This inferiority complex is not found among Germans, French, Japanese or Chinese. In India, the Bengalis, Tamilians, Telugu, Assamese, Nagas, Manipuris, Marathas, Gujaratis, and Sindhis are very firmly rooted in their mother tongue, and it is their preferred medium of communication. This list is not exhaustive and is based on my mental imprints through my interactions with speakers of these languages.

Brief Historical Perspective

Punjabi is the common mother tongue of the people of the Indus valley. This was the spoken language and was employed as a method of communication for ages. Guru Nanak Sahib chose the language of the masses -Punjabi to convey his ideas so that everyone could understand and incorporate them into their lives. The Gurmukhi Punjabi script adopted by Guru Sahib was based on Landa scripts. Successor Gurus compiled the hymns of saints and bards in various languages but incorporated them in Guru Granth Sahib in the Gurmukhi script. Guru Ji gave the masses spiritual insights in the language of the common man, instead of Sanskrit which was an exclusive domain of Brahmins. This was a revolutionary step in the process of dismantling the caste structure which had made others dependent on Brahmins for their spiritual, religious, and social needs.

Although Maharaja Ranjit Singh himself received little formal education, still he was a great visionary. During the 40 years of the Khalsa Raj of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1789–1839), literacy was almost 100%. All places of worship -Gurudwaras, Mandirs, and Masjids could only operate if they had a school attached to their precincts for imparting education. All women were literate in his kingdom. Despite the fact that the official court language was Persian, the Punjabi language was the mother tongue of the masses.

The Lion of Punjab’s strategy for educating the masses was through the Qaida-E-Noor -a basic primer for learning a language and related culture.

The Lion of Punjab’s strategy for educating the masses was through the Qaida-E-Noor –a basic primer for learning a language and related culture. After the annexation of Punjab in 1849, the British Indian government started planning the introduction of the modern European system of education with English as the medium of instruction as it was considered superior to indigenous languages. They realized that in order to succeed they will have to root out the Qaida system. To curb resistance, the British rulers made sure that nobody in Punjab could read their language. Anybody handing over a gun or sword to the Raj rulers was paid two annas while the one returning Punjabi Qaida was paid six annas. The colonial rulers collected Punjabi Qaidas from village to village and burnt them. Shahzad (2010) is of the view that the English rulers did not use Punjabi as a medium of instruction as they knew that by doing so literacy rate in Punjab will increase. It was strongly believed that educated people will come to know their rights and would challenge the rule of the invaders.

Today, unfortunately, we cannot even find a single copy of this historical Qaida. Though attempts are afoot to design and publish a modern-day Qaida-e-Noor, it has yet to become commonplace.

The British rulers made sure that nobody in Punjab could read their language as a means to curb resistance. Anybody handing over a gun or sword to the Raj rulers was paid two annas while the one returning Punjabi Qaida was paid six annas. The colonial rulers collected Punjabi Qaidas from village to village and burnt them.

In 1947, the Punjab was divided between India and Pakistan. Now a new national pride was awakening in these two nations divided on the basis of faith. To show their pride, Urdu was adopted as a state language in Pakistan and Hindi in India. The thrust to promote a language deemed as the national language over the entire country became a new reality in the name of integration. This newfound thrust was at the cost of the regional languages. Urdu in Pakistan and Hindi in India, along with English started to become the first language in homes, while the regional languages were considered the language of rural, rustic, uneducated masses.

The Punjabi language on the Indian side of the Radcliffe line received another jolt when Punjab was divided into Punjab and Haryana in 1966 when some territories of erstwhile Punjab were merged with Himachal Pradesh and the Union territory of Chandigarh was carved out. Hindi was adopted as the state language in Haryana, Chandigarh, and Himachal Pradesh, and the voice of Punjabi-speaking people in these territories was totally ignored. To rebuff Punjab, the state of Haryana, under Chief Minister Bansi Lal, who was viciously against anything Punjabi, adopted Telugu as the second language, despite the fact there were hardly any speakers of that language in the state. Significantly, even the Union government also did not intervene. Successive governments of all political parties in Punjab have not implemented Punjabi even under the three-language policy -Regional Language, English, and Hindi.

To rebuff Punjab, the state of Haryana, under Chief Minister Bansi Lal, who was viciously against anything Punjabi, adopted Telugu as the second language, despite the fact there were hardly any speakers of that language in the state. Significantly, even the Union government also did not intervene.

Globalization and the growing trend to immigrate out of India are further accelerating the lack of interest in Punjabi. As the immigrants are driven by the desire of bettering their lives, they quickly start assimilating into their adopted countries. As the parents want their kids to fit in, the mother language becomes low on the totem pole of life’s priorities. English has become the first language in many homes in the Diaspora.

Need to Preserve

A UNESCO report has clearly advocated the benefits of early learning in the mother language. The report says, “Research shows that education in the mother tongue is a key factor for inclusion and quality learning, and it also improves learning outcomes and academic performance. This is crucial, especially in primary school to avoid knowledge gaps and increase the speed of learning and comprehension. And most importantly, multilingual education based on the mother tongue empowers all learners to fully take part in society.”

The Gurmukhi alphabet which was derived from the Landa scripts has roots in the incredibly old Brahmi alphabet. The second Sikh Master -Guru Angad Dev Ji (1539-1552) enhanced the Gurmukhi alphabet to its current form for the express purpose of writing the revelations in Guru Granth Sahib, giving birth to the saying that it flows from the “Guru’s mouth.”

For the Sikhs, the survival of their language is not just a question of survival of their mother language alone, but preserving the key that opens the door to Guru’s spiritual wisdom and salvation. Thus, the stakes are much higher.

Now that doomsday alarms have been sounded, let us look at how to avoid this precarious scenario. Efforts will have to be made on multiple fronts. The first place to start the change has to be home. After all, if Sikhi has to survive today then the Sikhs need to get the Guru Ji’s message as written by them from its source in “Gurmukhi.” The translations, transcreations, and interpretations will always carry a personal understanding including biases or some taint. For the Sikhs, the survival of their language is not just a question of survival of their mother language alone, but preserving the key that opens the door to Guru’s spiritual wisdom and salvation. Thus, the stakes are much higher.

Let us explore some areas of how this can be pursued.

Using Music

The power of music is phenomenal. The newborn is sung rhymes and songs, to lull them to sleep as well as to teach them. No wonder Guru Nanak Sahib Ji employed the power of music to spread his message by singing his hymns to musical scales. In Gurdwaras the devotional singing called Keertan is the primary mode of spiritual discourse. Scientists have found that music stimulates more parts of the brain than any other human function. That’s why they see so much potential in music’s power to change the brain and affect the way it works. Punjabi music is very robust, catchy, and rhythmic. It has gained a strong following outside the Punjabi-speaking world. No social functions and weddings are complete without Punjabi songs. We need to ride on that interest wave and create a fresh interest in the Punjabi language. Traditional rhymes and folk songs can become effective tools for teaching the language and making it a preferred language of choice.

Storytelling

Language is the cultural glue that binds communities together and stories become its building blocks. The art of storytelling in family settings is declining, as the family units have metamorphosed from joint families to nuclear families with both working parents. However, the power of oral storytelling has not diminished. The power of storytelling can be used to promote and initiate kids into the language. We need to create more quality illustrated children’s books along with digital stories. We have a repertoire of traditional catchy folktales that have not been exploited as tools for teaching the language. We really need to get such resources developed and properly implemented to gain benefits from them.

Individuals and organizations have made some maiden efforts in this direction, but we need to raise the presentation and quality standards of these initiatives. More efforts are needed on how to disseminate these resources available to the learners for propagating Punjabi along with setting up their distribution centers. Even on the digital platform, there is a need to develop teaching tools.

Making Movies

Besides entertainment, movies provide avenues for cultural and literary immersion. They are an effective tool to impart to students a deeper understanding of the subject through audio-visuals. Movies can be used to supplement book reading for knowledge and creative thinking. We need a Satyajit Ray of Punjabi films who can take them to a higher level and gain global recognition, which will generate interest in learning the language.

Online Punjabi Teaching

There is an urgent need for imparting Punjabi language courses online. The Sikh Diaspora can take lead in setting up an online University imparting basic, certificate, and advanced courses in Punjabi.

Punjabi Learning Centers

We need to plan Punjabi Learning Centers in line with language teaching institutions like the Goethe Institute for German, Alliance Française for French and Confucius Institute for Chinese. No government is going to lead such an effort for Punjabi, so we will have to make our own efforts. These institutes running such programs provide us with a template and model on how it can be done. The syllabus, course duration, textbooks, and other resources need to be developed and standardized. We need to get organized and start, then plant the physical seed in some location. Then the model can be replicated in other cities, and it can be scaled up worldwide if we can get a proper organizational structure and setup. Besides teaching Gurmukhi reading and writing other courses such as Gurbani-Santhiya, Keertan, etc. can be added.

We need to plan Punjabi Learning Centers in line with language teaching institutions like the Goethe Institute for German, Alliance Française for French and Confucius Institute for Chinese.

Conclusion

We have to realize that raising children in an environment where Punjabi is the ordinary language of daily interaction is central to the survival of our beloved mother language. The onslaught of globalization on the fate of the languages without significant speakers is going to be their death knell. The irony of the times is that the pitch for the Punjabi language has to be made in English. Thus, the situation is grim, but not hopeless. It requires recognition of the situation we are facing and working on it in a concerted manner at the grassroots level.

There will be skeptics who may not believe in it, but I can vouch from my life experiences. My father and I were born in Burma (now Myanmar) and we spoke Punjabi and learned to read and write Gurmukhi at home. My kids were raised in the USA, and we had to put an effort to do it for their sake. Now my grandkids are on this path of learning. So, there is hope. We need to make a commitment and develop the requisite resources. The need of the hour is an author of the calibre of Bhai Vir Singh to inspire us with the love of our mother language and Guru’s teachings.We are world citizens and no language is despised by us, but we only exist when our mother tongue is revered by us as reflected in its usage by us.

We are world citizens and no language is despised by us, but we only exist when our mother tongue is revered by us as reflected in its usage by us.

Encouraged by sane voices amongst the community upholding the flag of Punjabi, irrespective of our faith and regional preferences, let’s rise for Punjabi. Let us not go down in history as the generation that was complicit in pushing Punjabi to extinction, but as the people that reversed the trend and made it flourish again.

References:

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/residential-school-band-class-action-settlement-1.6722014

- https://patch.com/connecticut/trumbull/history-of-punjabi-language–gurmukhi-alphabet

- Shafi Aamir. Punjabi Parents’ Perception of Punjabi as Their Children’s Mother Tongue. https://www.numl.edu.pk/journals/subjects/1566368197Punjabi%20Parents%2011.2.pdf

- UNESCO Report: Mother Tongue Matters: Local language key to effective learning, 2008. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/why-mother-language-based-education-essential

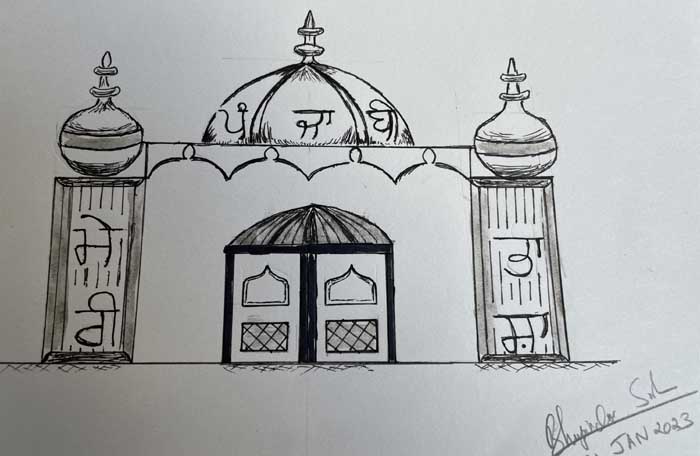

Note: Title image and other illustrations by the author.

An engineer by profession, hailing from Myanmar, educated in India, Bhupinder Singh is a Houston-based businessman, with a keen interest in writing books and articles on Sikh history, motivation and spirituality.

An engineer by profession, hailing from Myanmar, educated in India, Bhupinder Singh is a Houston-based businessman, with a keen interest in writing books and articles on Sikh history, motivation and spirituality.

One thought on “Punjabis can rejuvenate mother tongue Punjabi”