The Kashmir Files, Madeleine Albright & Basant in Khatkar Kalan

The Missing Files that We Need to Annex to the Movie Recommended by PM Modi — Kashmir to Khatkar Kalan tak Inquilab Zindabad bhee to karna hai

![The Missing Files that We Need to Annex to the Movie Recommended by PM Modi — Kashmir to Khatkar Kalan tak Inquilab Zindabad bhee to karna hai INDIA IS WATCHING The Kashmir Files, cinema halls are reverberating with patriotic slogans masquerading as abuse for Muslims, and the country is erasing certain histories of Kashmir and inventing new ones. And Madeleine Albright, who was once a child in war-torn Europe and was forced to flee her home, died on March 23. […]](https://www.theworldsikhnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Kashmir-file-copy-360x266.jpg)

INDIA IS WATCHING The Kashmir Files, cinema halls are reverberating with patriotic slogans masquerading as abuse for Muslims, and the country is erasing certain histories of Kashmir and inventing new ones.

And Madeleine Albright, who was once a child in war-torn Europe and was forced to flee her home, died on March 23. She was America’s first female Secretary of State, part of the Clinton cabal that busied itself fashioning a new world order, and was a mute witness to the Rawanda massacre.

The Sikh community in Punjab, and Sikhs worldwide, should be very interested in both these news cycles: the hype, hyperventilating nationalism and hate-spewing machine called The Kashmir Files row, and the persona of Madeleine Albright.

It is because Madeleine Albright wrote a part of The Kashmir Files that the Sikh community needs to engage with, Indians need to revisit, and the world needs to explore in all its dirty details.

Between Sikhs, Kashmir and Madeleine Albright, you will see many Kashmir Files, discarded into the recesses of our memory and lost in the bloody process of fashioning out a new Hindutva order.

Since The Kashmir Files comes highly recommended by India’s top film critic Narendra Modi—who is Roger Ebert, Pauline Kael, Francois Truffaut, Leonard Maltin, and a dozen more, all rolled into one—chances are that you have either already watched the movie, are planning to watch it, or have been listening to the high decibel debate and wondering if you should subject yourself to this cultural product dripping with nationalistic fervour and hate project at the same time, here is a humble suggestion: please complete your Kashmir Files with a set of three more piles of files.

The Chittisinghpora Files, the Pathribal Files and the Brakpora Files, all with the time stamp of “Spring of 2000 – Kashmir.” Indian history project wrote these files within the pace of a fortnight during the season Kashmiris call Sonth and Punjabis call Basant.

Madeleine Albright, by dying on March 23 and when The Kashmir Files is still running to packed houses, has drawn our attention to these three chapters in the history of Sikhs, Kashmir and India, thus making out a case for us to complete our Kashmir Files.

Here are the three files, one by one, each bloodied with gun shots, lies, deceptions, and state thuggery.

The Chittisinghpora Files —

Hours before the United States President Bill Clinton was to land in New Delhi for his India visit, unidentified gunmen in army fatigues lined up 36 Sikhs in front of two gurdwaras in the remote South Kashmir village of Chittisinghpora that did not even have a phone. One escaped with a gun wound, while 35 were killed.

It was the evening of March 20, 2000.

Clearly, some force was trying to send a message to Washington. Pakistan said Indian security forces were behind the massacre because India wanted to defame Pakistan, while the Vajpayee government claimed it was doing of Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizbul Mujahideen, both groups backed by Pakistan.

Clinton was still in India when the breakthrough came. A man called Yaqub Wagay, a Muslim resident of Chittisinghpora, had been caught. He had led the killers to the hapless Sikhs. By all accounts, Clinton must have been mighty impressed.

If he wasn’t, he would have been a couple of days later. Hours before Union Home Minister L K Advani was to visit the massacre site on March 25, 2000, about 11 miles from Chittisinghpora, in the village of Panchalthan, the army and the J&K police gunned down five LeT terrorists who, it said, were responsible for the Chittisinghpora massacre of 35 Sikhs.

Advani and then CM Farooq Abdullah were given a special presentation with help of site maps about how the operation was carried out.

The Patharibal Files —

Meanwhile, something else had happened. Five men had gone missing from two neighbourhood villages, Brarianagan and Halan, and Anantnag town. Their kin claimed they were taken away by army men in the middle of the night.

While the government had claimed that five LeT terrorists were killed in a five-hour-long gun battle, villagers were not aware of any such shootout.

Suspicion arose that the five killed in encounter and declared foreign militants could be the same five men abducted from their houses by the army. A villager from Pathribal, who saw the bodies of the men killed in the encounter, recognised one of them as Jumma Khan, one of the abducted men.

Anantnag saw processions by relatives of the five missing men. It became a major issue and the government was forced to order a judicial enquiry. There was no explanation why the five dead terrorists were buried in graveyards miles apart from each other.

The Brakpora Files —

Protestors, unsatisfied and angry, marched towards the deputy commissioner’s office on April 3, 2000, where CRPF and police opened fire, killing nine of them. Some of the dead were close relatives of the five missing villagers.

As the crescendo of protest rose, the J&K government suspended a couple of police officers, including the district police chief, and ordered that the bodies of the five men killed in the encounter be exhumed and DNA samples be examined.

The Exhumed Files —

On April 6-7, 2000, the days of exhumation, carried out in full public view, relatives narrated lists of what a particular dead man was wearing, the kind of ring a deceased had on his finger or the watch on his wrist. Every single detail they told about those still buried six feet under turned out to be true.

Among many others, Muzamil Jaleel of The Indian Express, a sterling journalist known for his courageous writings and a stickler to the ethics of the profession, was present at the exhumation site.

Novelist, essayist and award winning author Pankaj Mishra, who had reached Chittisinghpora within a day of the massacre of 35 Sikhs, describes the exhumation thus: “When the bodies were finally exhumed, almost two weeks after the murders, they were discovered to have been badly defaced. The chopped-off nose and chin of one man—a local shepherd—turned up in another grave. The body of a local sheep and buffalo trader was headless—the head couldn’t be found—but was identified by the trousers that were intact underneath the army fatigues it had been dressed in. Another charred corpse—that of an affluent cloth-retailer from the city of Anantnag, presumably kidnapped and killed because he was, like the other four men, tall and well-built and could be made to resemble, once dead, a “foreign mercenary”—had no bullet marks at all. Remarkably, for bodies so completely burnt, the army fatigues that they were dressed in were almost brand new.”

The DNA Files —

The truth about Patharibal was already out, but efforts were made to corrupt the evidence. Muzamil Jaleel reported how, on February 26, 2001, “the Hyderabad laboratory wrote to J&K Police, saying that samples supposed to be of a female relative of one of the victims actually belonged to a male.” Similarly, a sample supposed to be of a female relative actually turned out to be the blood of two different men. Initially, the government kept the scandal under wraps, but by the March of 2002, CM Farooq Abdullah told the J&K assembly that officials had indeed tampered with the DNA samples.

The Barakpora Firing Probe Files —

Justice S. R. Pandian Commission, set up by the J&K Government to inquire into the Barakpora firing incident in which nine people including relatives of Patharibal fake encounter victims were killed, indicted the security forces for “murder of peaceful protestors” and said these were clearly linked to the “faked encounter killings in Pathribal”.

The Official Confession Files —

The government, through then Deputy Commissioner of Anantnag, finally acknowledged the Pathribal encounter to be fake, conceded that victims were “innocent” and ordered grant of Rs 1 lakh as ex gratia relief to next of their kin.

The DNA Tampering Files —

On March 15, 2002, an inquiry into tampering of DNA evidence was ordered, and a senior doctor and others involved were suspended. Fresh samples examined by CFSL, Kolkatta established the truth behind the Pathribal fake encounter. Inquiry by Kuchai Commission found that forensic team and police had fudged the DNA samples.

The Milkman Files —

The entire police case was built upon a man called Mohammad Yousuf Wagay, who, the police had told Advani and media, had guided the “killers” to the village. His arrest within five days of the killings of 35 Sikhs was announced in New Delhi in full glare of the world’s cameras by none less than the Union Home Secretary Kamal Panday. It was on the leads provided by this Wagay guy that the police had engaged five “foreign terrorists” in a 5-hour-long gun battle, killing all of them.

Eventually, the Anantnag Police exonerated Mohammad Yousuf Wagay after months of investigation and reduced the charge from Section 302 for being an accomplice in the murder of 35 Sikhs to trying to disturb breach the peace (CrPC 107/151).

It was now clear that Wagay was framed, that the five men killed at Pathribal and dubbed as foreign militants were innocent local villagers abducted from their homes.

The Kashmir Files had turned very, very murky.

The Inquiry Files —

Seven months after killings of 35 Sikhs, CM Farooq Abdullah had announced a judicial commission headed by Justice Pandian. It was to inquire into Chittsinghpora massacre as well as Pathribal fake encounter. The good judge had completed his probe into Brakpora firing and linked it to Pathribal fake encounter, but the CM had a change of heart and decided there was no need to probe Chittisinghpora. Eventually, the Pathribal case went to the CBI in 2003 which took three years to finally clinch that it was a fake encounter and a “cold-blooded” plot by Indian Army officers.

Back to Chittisinghpora Files —

No one ever probed Chittisinghpora massacres. The CBI’s remit was limited to Pathribal. The clear conclusion is that no one wants to know the truth about Chittisinghpora.

At one stage, security forces claimed to have arrested two Lashkar militants Mohammad Suhail Malik and Wasim Ahmed, both Pakistani nationals, and recorded their disclosure about involvement in Chatisinghpora massacre. They were acquitted by the trial court, but the order was challenged in the Delhi High Court which again acquitted them in May 2012.

Eventually, and silently, they were repatriated to Pakistan. No one among the nationalists, including those recommending The Kashmir Files movie as the history of militancy in the valley, made any noise.

* * *

But we began narrating the entire saga because Madeleine Albright died on March 23 when Punjab was marking its tryst with Shaheed Bhagat Singh and vowing to usher in an Inquilab. The revolution has seemingly seeped into the Punjabi soul because we have learnt to ask tough questions of the powerful.

Speaking truth to power means asking, “Who killed the 35 Sikhs in Chittisinghpora?”

Ever since the massacre, Kashmir has remained agog with conspiracy talk. Much was published and talked about the language that the killers spoke, the names they used for each other, and how it did not have the hallmarks of acts carried out by Kashmiri terrorists.

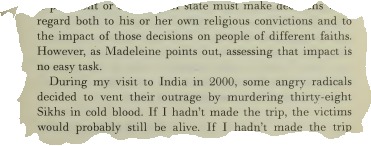

In 2006, Madeleine Albright, the highest-ranking woman in the history of American government at the time when she was US Secretary of State (1997-2001), wrote a book called “The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God, and World Affairs.” In its foreward, Bill Clinton wrote:

In 2006, Madeleine Albright, the highest-ranking woman in the history of American government at the time when she was US Secretary of State (1997-2001), wrote a book called “The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God, and World Affairs.” In its foreward, Bill Clinton wrote:

“During my visit to India in 2000, some Hindu militants decided to vent their outrage by murdering thirty-eight Sikhs in cold blood. If I hadn’t made the trip, the victims would probably still be alive. If I hadn’t made the trip because I feared what religious extremists might do, I couldn’t have done my job as president of the United States”.

When it became a matter of controversy, the publisher, Harper Collins, said the reference to “Hindu militants” will be removed in subsequent printings. Clinton’s office never commented on it.

Clinton’s Deputy Secretary of State, Strobe Talbott, who described his “fourteen meetings at ten locations in seven countries on three continents” with the then Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh in his book, “Engaging India,” also expressed serious American misgivings about the Chittisinghpora massacre.

“From the moment he got off the plane, Clinton spoke about “sharing the outrage” of the Indian people (but) did not endorse the accusation that Pakistan was behind the violence since the US had no independent confirmation,” Talbott writes in his book.

The Indian government never picked up a quarrel with Clinton, or Albright, or Talbott.

The apparent error was aggrandized by Clinton’s refusal to acknowledge it, and exacerbated by Pankaj Mishra’s book, “Temptations of the West: How to be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet and Beyond”, where he repeated the allegations against “Hindu Militants” even after the confession of the Lashkar-e-Toiba militant.

Pankaj Mishra weighs in on the issue of who killed the 35 Sikhs hours before Clinton’s visit:

“The Indian failure to identify or arrest even a single person connected to the killings or the killers, and the hastiness and brutality of the Indian attempt to stick the blame on “foreign mercenaries” while Clinton was still in India, only lends weight to the new and growing suspicion among Sikhs that the massacre in Chitisinghpura was organized by Indian intelligence agencies in order to influence Clinton, and the large contingent of influential American journalists accompanying him, into taking a much more sympathetic view of India as a helpless victim of Islamic terrorists in Pakistan and Afghanistan: a view of India that some very hectic Indian diplomacy in the West had previously failed to achieve.” {Death in Kashmir, by Pankaj Mishra, The New York Review, September 21, 2000 issue}

We still do not know who killed the 35 Sikhs during that Basant of 2000, but since there’s much talk of a revolution having been ushered in Punjab and people having learnt to ask questions to the powerful and speak truth to power, may be we can muster courage to ask.

After all, the country is busy learning the history of militancy in Kashmir and what happened to minorities in that Valley dominated by Muslims and seemingly infested by Political Islam’s jihadists, it is time to ask the old questions with a renewed fervour.

How else will The Kashmir Files be completed? The Prime Minister is very keen that we go and watch this movie in a theatre, and he has recently evinced a lot of interest in Punjab and in the welfare of the Sikh community. As Punjabis, and a people committed to Inquilab which becomes extraordinarily Zindabad in the vicinity of Khatkar Kalan, we must reciprocate and demand that The Chittisinghpora Files, The Pathribal Files and The Brakpora Files be annexed to The Kashmir Files so that we learn our history in a wholesome way. How else will we live up to our Rang De Basanti and our yellow turbans and our Inquilab Zindabad slogans and the framed photograph of the man hanging in every government office in Punjab?

After all, we are a people who have always held, across both sides of the Radcliffe Line, that Dhiyan Bhainan Sab Diyan Saanjhiyan Hundiyan Hun. (Daughters and sisters, our own and everyone else’s, deserve the same respect and regard.) It will be a shame if we cheat our understanding of The Kashmir Files of the highly important and sensitive annexure about mothers and daughters of Kunan and Poshpara, the twin villages in Kashmir’s Kupwara district. We must revisit those files for the simple reason that we also care about that jawan standing atop the Kargil hill. His repute cannot be allowed to be harmed, not even by those wearing regulation issue fatigues. The Kunan Poshpora Files have been gathering dust since 1991. They won’t make a film about them; it is time for you to google about them. Otherwise the Manorama Mothers in a different corner of the country will hold us to shame forever. Please do also read about The Manorama Mothers Files.

You have delved deep into The 1984 Files. You know what it means for some files never to make any progress, while others make it to the silver screen with a prime minister making favourable recommendations and the state making it tax-free.

The seasonal yellow headgear visitors to Khatkar Kalan might not utter a word about The Kashmir Files, neither will those who were first unconditionally with the ultra-nationalists and are now stuck in an existential crisis of their own, nor will the Congress which has stopped asking who killed Indian citizens in Gujarat in 2002, but what about you? You cannot afford to remain silent about the missing files. After all, Bhagat Singh is watching you. He is right up there, behind you, hanging from the wall. The martyr was an internationalist; he’s bound to have a conversation with Madeleine Albright. You’ll come up as a subject. They’ll probably discuss if you care?

Do you care? Please dust those files in your memory and ask hard questions to power. You did learn to ask questions, didn’t you? Remember your Andolan days?

(SP Singh is a Chandigarh-based senior journalist who has worked with major news agency/newspapers, has covered Punjab for more than two decades and anchors the cerebral political weekly debate on television, ‘Daleel with SP Singh’. His interests encompass politics, arts, society, academia, and yes, even trivia. He hardly plays ball with his hack cohort but has the balls to write stuff like this.)